Presenting Potentially Harmful Images in College Classrooms

Introduction

Like many teachers, I frequently incorporate digitized images into my classroom. Doing so provides students with a multi-sensory experience that can keep them engaged and help them remember important concepts. The increased availability of digital images makes doing so easier than ever before. Sometimes the images function simply as a visual backdrop to the lesson. Other times, I focus the discussion on a particular image or two, asking questions like: What do you notice? What is the creator of the image trying to convey? How do you know? How does this image relate to themes from readings or lectures? I have found that centering discussions of US history on images can help students integrate knowledge from other parts of the course and give me a better understanding of what ideas students may still be struggling to grasp.

But what about digitized images that could potentially cause harm? A history teacher could use a racist political cartoon, for instance, to facilitate discussion about a particular manifestation of America’s long history of white supremacy. However, doing so might also bury the visual image and its racist ideas into students’ subconscious. What about more harmful images, such as those that depict physical violence or suffering (often Black suffering)? Should teachers use potentially harmful images in their classroom? Is choosing to do so a form of “pedagogical violence”? And for teachers who do decide the benefits of presenting an image outweigh the potential risks, what are ways to ameliorate the harmful effects?

This post draws on my experience of viewing lynching photographs as an undergraduate student and how my thinking about the merits of teaching with such images has evolved. I suggest that teachers need to think critically about what images they use in class. While potentially harmful images can provoke a productive discomfort, the decision to show them should never be taken lightly. Instructors must reflect on how various images may be received by their different students and consider how presenting harmful images can prioritize the learning of some students over others. Instructors should not create situations that reproduce and inflict harm on marginalized students. Often, the best solution is simply not to show the image. Instructors who do decide to provide an opportunity to view such images should do so with care and context that helps undermine the potential harm.

Lynching Photographs

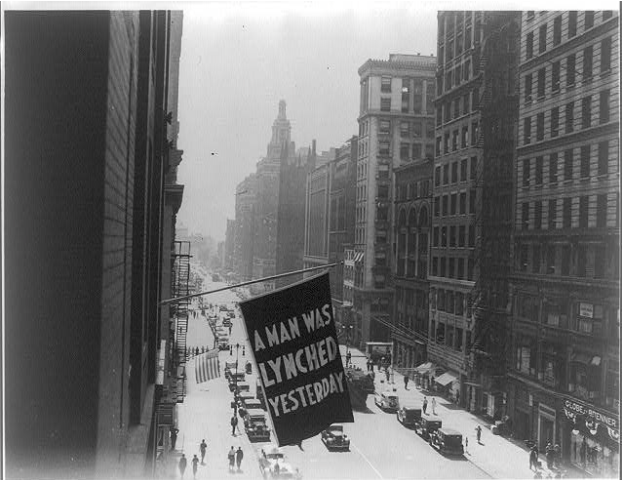

While historic photographs of lynchings are perhaps an extreme example, their history demonstrates the complicated nature of whether good can come from harmful images. Created and circulated initially by white Southerners who wanted to commemorate the event, lynching photographs dehumanized Black people and helped cement segregation. Interestingly, however, around the end of the nineteenth century, Black journalists like Ida B. Wells also began to circulate photographs of lynchings. While Wells could not completely eliminate the dehumanizing power of the photographs, she presented the harmful images in a way that increased the likelihood that the audience would interpret the images as she saw them: as ghastly representations of white brutality. In doing so, Wells used the images to generate support for the anti-lynching movement.

Contemporary scholars who present these horrific images in books such as Without Sanctuary or in classrooms imagine themselves as operating within this anti-racist tradition. For instance, Amy Louise Wood and Bridget R. Cooks have argued separately that if such images are presented in a particular way they can incite an intense sympathy that moves the viewer to confront the legacy of racist terrorism and its contemporary manifestations.

My Memories

I can still remember my first experience of viewing a photograph of a lynching. I was sitting in a lecture about the history of religion in America, and we were discussing Donald G. Matthews’ “The Southern Rite of Human Sacrifice.” I think the professor warned us about the photograph, but I don’t honestly remember. I do remember the feeling of revulsion upon seeing it. The photograph, a postcard that white Southerners had used to commemorate the event, was one of the most disgusting and depressing images I had ever seen. After class, I briskly walked to the bathroom to throw up.

I was repulsed by the image for multiple reasons. First, the photograph was truly gruesome. The victim’s mutilated body looked like nothing I had seen before. But I also think that, as a white student, I was experiencing a degree of pain that bell hooks notes often accompanies “giving up old ways of thinking and knowing.” I was nauseated in part by my overwhelming feelings of shame at seeing smiling white people in the foreground of the photograph. Those smiling faces could have been my ancestors. The image forced me to come to terms with the brutal reality of American white supremacy, a reality that I knew intellectually but had not fully felt. I unlearned my white innocence, if only for a moment, and that was not comfortable. In hindsight, I also wonder if my expressions of discomfort were an unconscious attempt to differentiate myself from the white people in the photograph. I was different from those bad white people… right?

Lasting Effects

The experience stuck with me. Once you see an image like that, you cannot unsee it. Looking back, the experience of viewing the image may have shaped my historical and political interests. The next semester, just a few weeks after the murder of Trayvon Martin, I wrote a research paper about lynching and the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. As the great-grandson of a white MECS minister, I had to know—did religious beliefs affect whether people participated in such atrocities or in the movements to halt them? Writing that paper convinced me that looking to the past offered important lessons that could inform how we respond to contemporary injustices and set me off on the journey to becoming a historian. While it is impossible to know for sure, I wonder if the image also cemented my personal and professional commitment to anti-racism. For many years, I concluded that I was significantly better off for having seen the photograph that day.

But reading work by scholars such as Saidiyah Hartman has led me to question that conclusion. Did viewing the spectacle of suffering through the camera lens of a lynching participant render me just another spectator of the lynching? Did my looking “reproduce, rather than interrupt, the power relations of (black) lynching victim and (white) lynching spectator,” as Wendy Wolters has argued? I cannot help but reflect on how differently I experience lynching photographs when I see them now, a decade later. While lynching photographs still make me queasy, I no longer experience the same degree of physical revulsion when viewing them. This change over time reminds me of Hartman’s warning that “Rather than inciting indignation, too often [reproducing spectacles of Black suffering] immure us to pain by virtue of their familiarity.” Did viewing the photograph desensitize me to Black suffering? I don’t know, but I hope not. Hartman and Wolter’s insightful critiques mean I can no longer look back at the classroom viewing as wholly beneficial. Still, I cannot shake the sense that the viewing was an important and net-positive experience for me. But I wasn’t the only one who viewed the image that day.

In the years since, I have increasingly wondered how my Black classmates felt about the experience. Unlike white students like me, most of them likely did not need our classroom viewing to learn and feel the brutal reality of the history of lynching. As James Cone has written, Black Americans “cannot forget the terror of the lynching tree no matter how hard we try. It is buried deep in the living memory and psychology of the black experience in America.” If that’s the case, did Black students learn anything from viewing the spectacle of suffering that day? Or was it a potentially retraumatizing lesson they had to endure for my sake? I am curious if any Black students would have felt comfortable asking our white professor to opt out. And what did it feel like to view the photograph in a classroom surrounded by mostly white classmates? What, if any, were the lasting effects of viewing that image for Black students and other students of color?

Choosing (Not) to Show Harmful Images

Making a choice to teach with images that could potentially cause lasting harm should never be taken lightly. Images are powerful. Lynching photographs were originally created to dehumanize Black people, and they still can today. Harmful images that do not depict physical violence can also dehumanize. Instructors need to think critically about the merits and dangers of showing potentially harmful images before doing so. Such images can force students to sit with discomfort that is essential for learning. But classrooms should never be sites of “trauma porn.”

White male instructors like me need to be especially mindful of our positionality as we select images to show in class. If I do not carefully consider each image and the different ways it might be received by my diverse students, I can end up selecting images that unintentionally privilege the education of students who look like me. But the education of white students, even if it’s teaching them to give up “old ways of teaching and knowing,” cannot come at the expense of Black, Native, Latinx, Asian, or other students of color.

I recently experienced this dilemma while delivering a lecture on the history of the American West. The topic is not my specialty, but that’s normal when teaching the US history survey course. I initially included a photograph of the Wounded Knee Massacre in my powerpoint. I knew the image might be especially shocking for my white students who were more likely to be ignorant of the long and ugly history of native displacement. I hoped that the feeling of shock might disrupt the American exceptionalism that so many white kids like me grew up with.

Upon reflection, however, I decided to replace the image with a recording of a powerful poem by Autumn D. White Eyes about the struggle to commemorate ancestors who died at Wounded Knee. As the poem ended, I faded in Raye Zaragoza’s song about the Standing Rock protests, “In the River.” I hoped the song’s instrumental opening would provide students the space to let Autumn D. White Eyes’ words sink in, as well as to encourage students to draw connections between the past and the present.

The experience reminded me that giving careful consideration to the images I show in class can be challenging. It took one Google search to find the disturbing Wounded Knee photograph. It took significantly more intentionality to find the poem and song. But I am so glad I took the time to think it through and make the change. By replacing the shocking image with the poem and song, I highlighted Native resilience rather than the spectacle of Native pain.

How to Show Harmful Images

In the moments when teachers do decide to show potentially harmful images, we need to think critically about how to do so. As a graduate instructor for an American Studies course taught by Grace Hale, I observed a potential model for how to do so while maintaining what Catherine Denial has called a “pedagogy of kindness.” The class before she discussed the images, Hale warned students what was coming, and she told students they could miss without penalty if they felt it would be too traumatic. She provided ample context to help students understand the photographs, and she focused her lecture not on Black suffering but on the crusading Black journalist and activist, Ida B. Wells. Furthermore, Hale encouraged TA’s like me to reserve time in the following discussion section for students to reflect on the learning experience, an experience Maggie Melo has described as a “time for healing.” In a smaller environment, students were able to process what they had seen and learned.

Precautions such as these do not eliminate the inherent risks of showing potentially harmful images. But they do serve an essential purpose: by leading with care and context, instructors can help minimize the images’ potential harm.

Takeaways

- Ask yourself if showing the potentially harmful image is truly necessary. Does presenting such images prioritize the learning experiences of white students over their classmates of color? Are there ways you can convey similar ideas without showing the image?

- Reflect on how these images fit with the rest of your course. Are most of your discussions of marginalized groups focused on pain and trauma? If so, consider how you might emphasize narratives or images of resistance, resilience, or joy.

- Provide students a chance to opt-out of the in-class viewing. Better yet, due to classroom power dynamics, try framing this as an “opt-in” rather than an “opt-out” experience. Try listing that day as “optional” on the syllabus or consider scheduling a time outside of your regular class session.

- Prepare your students beforehand. Provide ample context for what students will be seeing before presenting the images. Again, this context can frame how your students experience these images and help undermine their dehumanizing potential.

- Clearly state and contextualize the dehumanizing work that the image is doing. Remind students of the personhood of those being represented in the image.

- Maintain a posture of care. Share about your experience viewing the image and acknowledge that the experience of viewing the image will be different for different people. Though it can be harder in larger classes, be sure to check-in with your students before, during, and after the experience. Consider using small groups or “free writes” to provide students a more intimate space to process what they are learning.

- Keep working at it. Giving careful consideration to the images you use in class takes time and persistence, but it’s worth it!