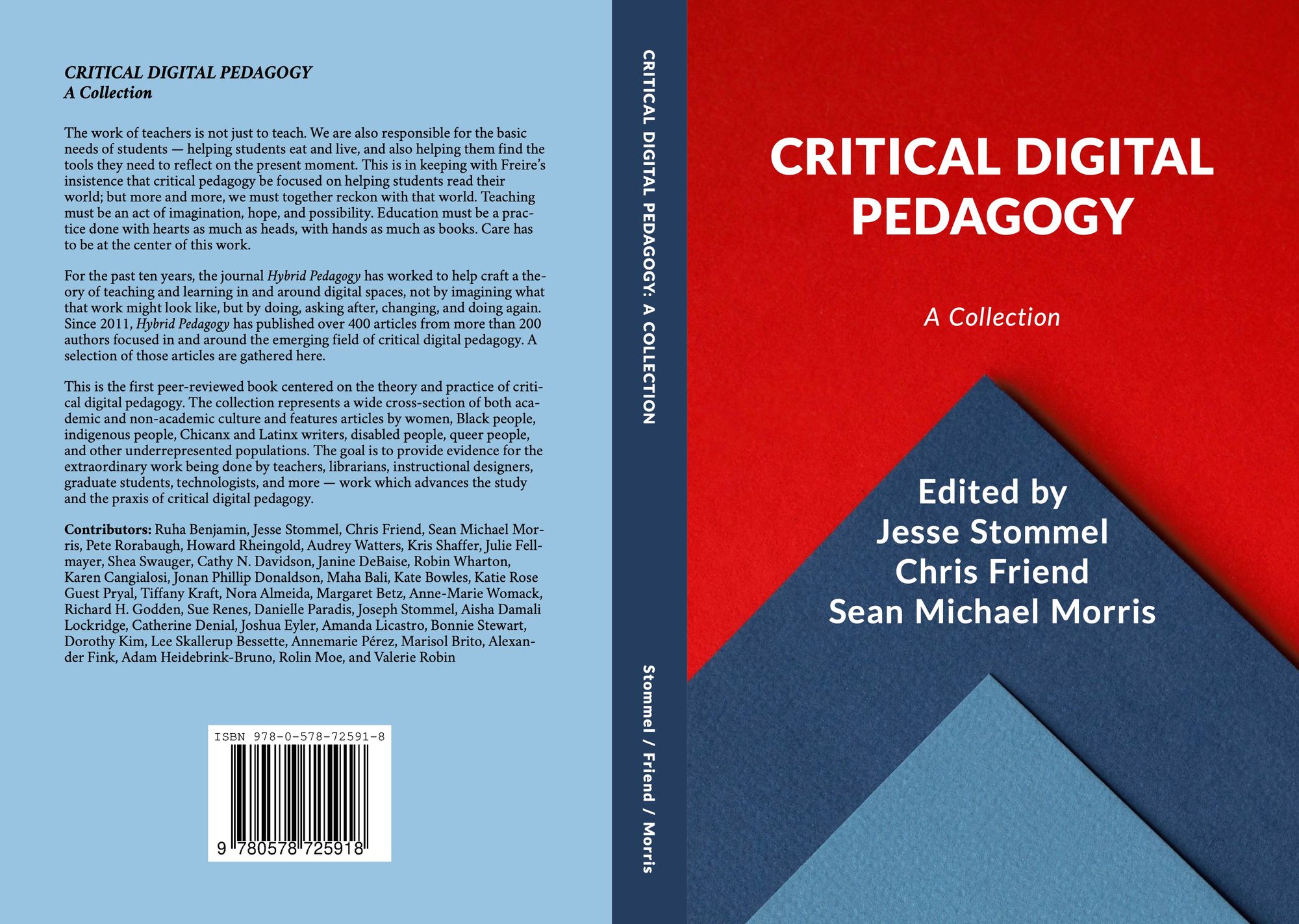

This piece was revised and expanded for a book from Hybrid Pedagogy, Critical Digital Pedagogy: A Collection, available now in paperback and Kindle editions.

In the past two years, when I’ve been asked to sum up my approach to pedagogy, I’ve said “kindness.”

I didn’t always think this way. My graduate education encouraged me to think of students as antagonists, always trying to get one over on their instructors. I was urged to be on the lookout for plagiarism, to be vigilant for cheaters, to assume that the students wouldn’t do the reading, and to expect to be treated as a cog in a consumerist machine by students who would challenge their grades on a whim. I was once advised by a senior graduate student to “be a bitch” on the first day of class so that my students never wanted that version of myself to show up again, advice that I dutifully repeated to several of the graduate students who came after me. I was a stickler for deadlines, and memorably once refused to excuse the absence of a student who was battling a burst pipe in his house when class was in session. I look back on that now and wince.

I gradually learned, through a great deal of trial and error, that this combative way of approaching teaching was counterproductive at best, destructive at worst. Students didn’t communicate with me easily, since many of them didn’t see the point. They knew (I realize now) that I approached them with suspicion, and so returned that sentiment in kind. It quickly became clear to me that I needed to build relationships, not defensively prevent them from forming, and that trust was a vital part of creating the circumstances under which learning could happen. There was no space for trust to grow in the learning spaces I’d been trying to create, and so I learned to ease up, to let go of rigid control I’d tried to impose upon the classroom, and to make room for the unpredictable and unexpected. I thought, twenty-three years into my teaching career, that I was doing a pretty good job. And then I went to the Digital Pedagogy Lab Institute at the University of Mary Washington in the summer of 2017.

The entire Institute was predicated upon the concept of kindness. From the pronoun buttons available at the registration desk, to the probing questions of the session leaders, to the time people took, one-on-one, to talk about syllabi and assignments, there was an ethos of care running through the whole four days of my residency. I had signed up for the Intro track, and had expected to spend my time evaluating digital tools to bring into my classroom. I did do that, but first I was asked to think about why I needed those tools at all, whom they would serve, and how I would build in accommodations for students with disabilities. My fellow attendees and I were constantly asked to consider why we were doing things the way we were, and what subtextual messages we were sending to our students about who they were. I took a good long look at my syllabus, and realized I had communicated everything in it from a position of absolute authority. The language I used to describe the college’s Honor Code, for example, expressed the suspicion that everyone was going to commit some awful academic offense at some point, and my attendance policy made no room for the idea that my students were adults with complicated lives who would need to miss a class now and again.

Why? Why did I posit my students as passive novices who couldn’t contribute to their own learning? Why did I require students to jump through hoops to prove that they deserved an extension on a paper? Why did I dock points if my students missed three classes in a term? No one had ever asked me to defend my pedagogical choices before, and once they did, I found much of my pedagogy indefensible. I felt regret and no small amount of embarrassment. My teaching was undone by the presence of a question that was never articulated quite this directly but was everywhere around me:

Why not be kind?

And so I chose kindness as my pedagogical practice. Telling people this has often elicited a baffled response. Kindness is something most of us aspire toward as people, but not something we necessarily think of as central to teaching. In part this is an effect of the pressures that are brought to bear on our classrooms from outside them, symptomatic of a nationwide clamoring (in some circles, at least) for standardization, testing, and rote assessment. Instead of kindness, we’re more likely to hear about standards and rigor. (The national professional organization to which I belong says that “good teaching entails accuracy and rigor,” but never mentions compassion, for example.) And when we are urged to be kind within an educational setting, it’s too often to make up for a lack of institutional support for students and faculty in need, asking a particular service of women and non-binary individuals of all races, and men of color. Kindness can be a band aid we’re urged to plaster over deep fissures in our institutions, wielded as a weapon instead of as a balm. And too often people confuse kindness with simply “being nice.”

But, to me, kindness as pedagogical practice is not about sacrificing myself, or about taking on more emotional labor. It has simplified my teaching, not complicated it, and it’s not about niceness. Direct, honest conversations, for instance, are often tough, not nice. But the kindness offered by honesty challenges both myself and my students to grow. As bell hooks memorably wrote in Teaching to Transgress, “there can be, and usually is, some degree of pain involved in giving up old ways of thinking and knowing and learning new approaches.”

Yet in practice, I’ve found that kindness as pedagogical practice distills down to two simple things: believing people, and believing in people.

When a student comes to me to say that their grandparent died, I believe them. When they email me to say they have the flu, I believe them. When they tell me they didn’t have time to read, I believe them. When they tell me their printer failed, I believe them.

There’s an obvious chance that I could be taken advantage of in this scenario, that someone could straight-up lie and get away with it. But I’ve learned that I would rather take that risk than make life more difficult for my students struggling with grief and illness, or even an over-packed schedule or faulty electronics. It costs me nothing to be kind. My students have not, en masse, started refusing to meet deadlines, but the students who are struggling have had time to finish their work. My students have not, en masse, started skipping class, but they’re not required to undergo the invasive act of telling me personal details about their lives when they can’t show up. My students have not, en masse, started doubting my abilities or my expertise, but they have stepped forward to direct their own education in meaningful and exciting ways that I could not have thought of.

That’s believing students. But what about believing in students?

Believing in students means seeing them as collaborators — believing they have valuable contributions to make to the way in which syllabi, assignments, and assessments are designed, and life experiences that should be respected in the classroom.

In Fall 2017, I asked both classes to give me questions about the topics we’d be covering — American Indian history in one class, and the history of gender and sexuality in the U.S. in the other. I was then able to craft a syllabus for each class that wove together my own sense of important historical context together with answers to the questions they had posed. The students were offered a sense of ownership in the course, and I was alerted to things I might not otherwise have considered — basic terminology around which there was confusion, for example, or, say, a strong interest in understanding changing concepts of masculinity over time.

I drew on the wisdom of teachers who had gone into this ‘kind space’ before me, and made significant changes to the way in which I graded work in those classes. Rather than distributing a finished list of grade requirements, I shared some suggestions, and refined those with my students’ input until we’d reached a consensus about meaningful assessment. When my students turned in a paper, they also filled out a self-evaluation of their work that asked them what they’d do differently next time, how pleased they were with what they produced, and what they learned about themselves. These adjustments are possible in any class, be it one like mine, with twenty-five students, or a much larger lecture course at a different kind of institution. Both approaches give students greater ownership over their grade and the way that it’s awarded; grading becomes, to whatever degree possible, a collaborative venture. In smaller classes it’s possible to go further; my students and I sat together and talked over the answers on their self-evaluation, and I asked my students to give themselves a grade. Together, we entered into a conversation about why that grade felt right to them, and why it did or didn’t feel right to me, before reaching a consensus on what grade they’d earned.

I’ve also begun to think of my classes in terms of universal design. For many years I taught with the idea that there was a well-established, academic norm that was fair and impartial, and my job was to make accommodations available for those students who had particular disabilities, or faced particular challenges in meeting that norm. I no longer believe in such a practice. My job, as I see it now, is to make my classroom accessible to everyone. I’ve begun the long work of redesigning my lessons and assignments so that everyone is a full participant, and no one needs ask for extra time or a note-taker, because those needs have already been addressed. Because I don’t believe students with disabilities should have to out themselves, I no longer ban laptops in my classroom, or have quizzes that some students have to take across the hall to get their necessary time-and-a-half. Instead I’ve experimented with take-home quizzes, options for students to record videos as well as write papers, and final project guidelines that allow students to create anything that will demonstrate to me what they’ve learned over the term. This, too, is about belief in my students, and believing that by designing my class to accommodate all types of learning I’m demonstrating something important about the ways in which we should be creating a more just world.

I feel more comfortable as a teacher now than I ever have. The subconscious sense that students were antagonists lingered inside me for a long time — long enough that it has been a marvel to teach these past two academic years and experience a teacher-student relationship without that default expectation. I was less stressed; I didn’t have reservations about walking into the classroom. My students rose up to meet every new challenge I presented to them, and vocally affirmed that they appreciated the new approach to grading. Crucially, they articulated that when I looked them in the eye and told them what they had done well in a paper, they believed me, whereas when the same info was written at the end of a paper, they didn’t. They saw it as pablum — something that I had to write before I delivered the bad news of what they could still work at (which they interpreted as “what I did wrong.”) I see that shift, from their exasperation and disappointment to them becoming partners in the assessment of their work, was emblematic of the fruits of a pedagogy of kindness. It was, and is, transformational for all involved.

A pedagogy of kindness asks us to apply compassion in every situation we can, and not to default to suspicion or anger. When suspicion or anger is our first response, a pedagogy of kindness asks us to step back and do the reflective work of asking why we’re reacting in that manner and what other instances of disappointment or mistrust are coming to bear on a particular moment in a particular student-teacher interaction. This can transform the student-teacher relationship — but it’s not only on an individual-to-individual level that it can alter our working world. To extend kindness means recognizing that our students possess innate humanity, which directly undermines the transactional educational model to which too many of our institutions lean, if not cleave. Transactional models of education identify students as consumers and teachers as retail workers who must please their customers (an inhumane model for retail sales as well as the world of learning). Administrators become managers in this model, looking for cents they can save rather than people they can support. This drains the entire system of its humanity, and leads to decisions at every level where the personhood of a student, teacher, or administrator is diminished.

To value and practice kindness is to resist such models. Even where institutions are leaning away from investment in personhood in favor of hedge funds, we as teachers have the ability to insist that individuals matter. We have the means to hold a line, to see the student without shelter — or food, or safety, or a laptop, or an internet connection, or health, or confidence, or a support network — as someone who matters exactly as they are and even because of the challenges they face. We can refuse to dehumanize our students and presume an adversarial stance. We can prioritize kindness.