There was a definite buzz in the room on an otherwise ordinary Friday morning. Faculty, administrators, librarians, and educational technologists had gathered to hear future plans for our university’s classrooms. A communication professor described an assignment in which students reflected on their semester working through issues of race and class by using Comic Life to narrate their experience in short graphic novels. A history instructor explained how the free online tool Storify would help her students connect questions of historical memory with current headlines over the sixteen weeks of her class. A rhetoric professor dreamed aloud about working with students to build a participatory archive that collected popular representations of pregnancy for scholarly annotation, analysis, and remixing. The energy and nature of the conversation were extraordinary. Ideas flowed across disciplinary lines. Librarians pushed humanities professors toward different ways of thinking about archives. Political scientists and foreign language instructors swapped strategies for improving assignments.

The setting was the showcase presentations for the Digital Humanities and Social Sciences Institute, a six-week training seminar for faculty on our campus, James Madison University. Participants from five disciplines across the humanities and social and health sciences were presenting assignments they had worked on over the previous six weeks alongside readings, discussions, and workshops based on DH research and pedagogy. The institute was designed by Seán, a writing studies professor, and Andrew, a history professor, and we have co-taught it three times over as many years. Among the greatest challenges we have faced in introducing newcomers to the digital humanities is the sheer diversity of the field. Digital humanists orient their work variously around research, pedagogy, theory, and methodology. Many, in fact, argue that DH is better understood as a variety of methodological approaches to humanities questions than as a unified field. Another important challenge for us has been charting an approach to the digital humanities that fits with our particular kind of institution: a mid-sized public university with an undergraduate focus and a strong commitment to teaching and the liberal arts.

Spurred on by these challenges, we have developed a DH pedagogy based upon a framework of values — critical thinking, collaboration, production, and openness — that we call our “CCPO” framework (see the infographic below). Over the past three years of teaching the institute, we have found that this values-based pedagogy accommodates and actually draws strength from the diversity of DH, leveraging the lack of clear definition that initially made introducing DH so challenging, and even advancing new forms of interdisciplinary practice. While the energizing, collaborative atmosphere of our Friday morning showcase presentations felt effortless, it was in fact the fruit of this values-based approach to DH pedagogy at the undergraduate level.

The values in our CCPO framework are well-represented in much of the DH literature, and they speak to the consistent call that DH is not just about doing the humanities digitally, but is a means of transforming how we theorize and practice the humanities more broadly. Using the growth of our institute as a backdrop, we want to explore how our CCPO framework might make good on that promise of transformation, particularly at institutions such as ours. While we and others have found the CCPO framework to be valuable for students in the courses we teach, our focus here is on our work with faculty and staff and its implications for larger discussions about DH pedagogy and the place of DH on liberal arts campuses. As Bryan Alexander and Rebecca Frost Davis suggest, liberal arts institutions often avoid or find it difficult to sustain digital humanities projects, largely because DH often comes in the form of resource-intensive centers and with a strong, graduate-focused research mandate that do not always align well with undergraduate, teaching-focused campuses. However, a liberal arts focus aligns well with DH, and we believe our CCPO framework might serve as a values-driven yet practical way to bridge DH and the liberal arts on campuses where DH might not ordinarily take hold.

Valuing Values in DH Pedagogy

There are compelling reasons for digital humanists from all types of institutions to define their work around values. In her article “This Is Why We Fight,” Lisa Spiro calls for digital humanists to unite around core values rather than “particular methods or theoretical approaches.” Spiro argues for a values-driven understanding of DH mainly because it promises to make room for all sorts of practitioners, including those primarily interested in coding, theorizing, or teaching. Focusing on what unites DH rather than who is “in” and who is “out,” she suggests, facilitates cooperation in facing common challenges. Unlike an ethics statement, which tends to demarcate standards and the behaviors that might reach those standards, Spiro notes that a values statement is somewhat broader — a grounds for conversation and debate. A values-driven understanding of DH is therefore particularly useful on liberal arts campuses because it can successfully invite dialogue about how DH might connect with and advance the local institutional mission even when the relationship is not always readily apparent.

Spiro’s own proposed set of values — collaboration, openness, collegiality and connectedness, experimentation, and diversity — certainly inspires our own set of values and are threaded throughout our CCPO framework. However, our values-driven project differs somewhat from Spiro’s, which by design addresses all institutional contexts. We have crafted and clarified CCPO over time such that its values are tailored to our kind of institution, and more specifically to our own university, which particularly prizes teaching, undergraduate research, and community and civic engagement. Our decision to lead with pedagogy-driven values reflects our commitment to an understanding of DH in which pedagogy is central rather than peripheral. It is also tactical, taking advantage of the inherent flexibility of DH to increase the chances it will connect on our teaching-focused campus. As Ryan Cordell has noted, “we must think locally, and create versions of DH that make sense not at some ideal, universal level, but at specific schools, in specific curricula, and with specific institutional partners.” Our value system is remixed from a larger set of ideas common to DH conversations to suit our aims, and is similarly open to and invites remix to suit other contexts and goals.

With this sensitivity to context in mind, it is worth briefly contextualizing what each of our CCPO values entails. At first blush, “Critical Thinking” might seem like a throwback to a more traditional framing of the humanities as a mode of analysis and critique in comparison to DH’s emphasis on doing and building. Tom Scheinfeld and Matt Kirschenbaum frame the digital humanities as being primarily about method over theory; similarly, Burdick et al.’s suggestion in Digital_Humanities that the project is the primary unit of analysis in DH foregrounds the field’s emphasis on building knowledge from the ground up. While we embrace this shift from theory to method, and gloss critical thinking as a kind of critical doing in our institute discussions, we nevertheless find critical thinking to be a useful value within the parameters of our institute. We are working with faculty from many disciplines, most of whom are new to DH, and many of whom are new to digital technologies beyond content management systems such as Canvas. We have discovered that critical thinking can be used as an effective bridging mechanism between the modes of thinking with which our colleagues are familiar and the more production-oriented practice of DH. Jeffrey McClurken’s “digital toolkit” concept helps participants make this leap. McClurken notes that an important part of digital literacy is a “willingness to experiment” with a wide range of tools, and to “think critically and strategically” about which tools will best serve the aims of a particular digital project. Asking students to select from, or even assemble, their own “digital toolkit” (rather than simply working with assigned tools) makes tooling a focal point of critical reflection.

Collaboration is not only a key term in the digital humanities, but also a cornerstone concept in higher education. Many disciplines view it as a valuable research topic in its own right, and the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) provides a varied interdisciplinary research platform for weaving collaboration into pedagogy. DH values collaboration for many of the same reasons, and our institute discussions often explore the promises and challenges of engineering intensive collaborations among students. Our institute also offers participants an expanded understanding and practice of collaboration rooted in DH’s preference for interdisciplinary inquiry. Through class visits and workshops, we introduce faculty participants to a wide range of potential collaborators who might help them realize their assignment designs. On our campus, experts in technology, instructional design, assessment, and intellectual property are not part of a single organization. Having other stakeholders participate in the institute helps participants build their assignments, an aspect of the institute that is highly valuable, according to our evaluations. Beyond its immediate utility, this method provides a practical way of building a DH culture on campus. Bryan Alexander and Rebecca Frost Davis have observed that “unbundling” the dominant research center model in favor of a networked approach may be a favorable strategy for nurturing DH in liberal arts institutions like ours. It fosters coalitions of like-minded colleagues across campus, and draws on existing computing resources to promote DH-oriented projects.

Production is a challenge on liberal arts campuses. DH as a field takes production seriously; indeed, many large-scale projects build the tools in-house to accomplish the project’s goals. While we introduce and discuss such projects, we tend to “distill” their high-tech approaches into tools and methods more suited to the undergraduate classroom. For example, after showing the website of a sophisticated text-mining project from the Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of Richmond, we introduced Google’s Ngram Viewer, which lets users graph the incidence of words and phrases over time across its vast collection of digitized books. Most of the tools we introduce, including Storify, Thinglink, Comic Life, and Canva, are inexpensive or free and easily learned. We also throw into the mix more ambitious tools, such as the Omeka platform and its image annotation plugin, Neatline, that are supported by our Center for Instructional Technology. This approach aligns with Adeline Koh’s proposal that DH should make room for relatively easy technologies that allow humanists to stay true to their core skills and priorities, including pedagogy. By offering a way to introduce DH methods into the undergraduate classroom without toppling the curricular goals of the course or placing unrealistic demands on instructors, thoughtfully simplified tooling makes it possible for digital techniques such as topic modeling, distant reading, and spatial analysis to infuse and invigorate humanities pedagogy.

While each of the CCPO values overlap, we have come to understand openness as a kind of overarching value that informs and even transforms the others. Openness invites attention to open-access scholarship and tools, intellectual property, and accessibility. Most importantly for the goals of our institute, openness asks instructors to consider expanded audiences for student work. As participants build their assignment designs, we ask them to think about the reach of the work, in particular an audience for the assignment beyond the classroom and the final appraisal of the instructor. What work does this assignment do in the world? The straightforwardness of this question belies the difficulty of the challenge it poses. Asking our instructors and students to open their class-based learning to media-rich work for broader publics clearly raises the stakes of an assignment. This understanding of openness can also push against the temporal bounds of the semester: if the work produced by students will exist beyond the end of the class, can it be picked up by future iterations of the class (or other classes) for further development?

CCPO in Practice

A brief look at several assignments will indicate the potential of the CCPO framework. Reflecting the flexibility of the framework, the digital assignments that participants in our institute develop range from simple and manageable to complex and ambitious, but always address one or more of the CCPO values. Gianluca De Fazio (Justice Studies) aimed to foster critical thinking and improve class discussion by asking his students to use Coggle, a free mind-mapping tool, to outline course readings. Focusing on collaboration, Besi Brillian Muhonja (Africana Studies) conceived a project in which her students will work with university students in Kenya over several semesters to digitally map motherhood in Africa. Drawing attention to the power of the tools we use to shape the stories we tell, Vanessa Rouillon (Writing, Rhetoric, and Technical Communication) asked students to produce a short video that visually presented their findings from a previously completed research paper.

Professor Steven Reich, who teaches sections of History’s core course in research methods (HIST 395), incorporated all four of the CCPO values. Working with Andrew, he designed an assignment in which students share their research findings in an NPR-style podcast called STUDIO 395. Students interview one another about the topics of their research papers and host their own page on the class website, building images and text around an intriguing research question. The assignment asks students to think critically about audience as they practice communicating their findings to the public. It opens new possibilities for collaboration, both within and across semesters. Following a successful pilot, the project was taught during the Fall 2015 semester by four other History faculty members to more than fifty majors.

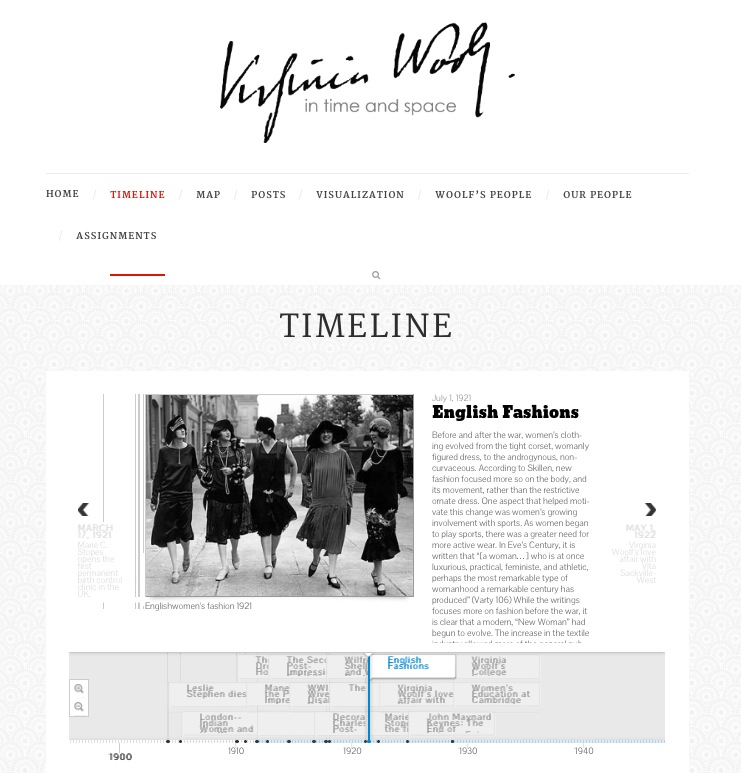

All four CCPO values are similarly evident in Virginia Woolf in Time and Space, a website developed by English professor Siân White and her students. Students critically engaged with the Bloomsbury formalists’ interest in non-linear textuality by composing posts on a variety of topics and then collaboratively remixing those posts into timelines and maps. Using tools such as Canva, Thinglink, and Prezi, students also produced compelling visual arguments about aspects of Woolf’s novels. Finally, the project’s commitment to openness can be found in its publication on the web, as well as collaborations with the university’s Center for Instructional Technology, the department’s library liaison, and the Digital Communication Consulting Center.

Moving Forward

Assignments such as these encourage the cross-fertilization of ideas, modes, methods, and disciplinary worldviews that, with careful nurturing, could grow into a solid and recognizable pattern of interdisciplinary DH practice on our campus. Following Virginia Kuhn and Vicki Callahan, we believe that such work can be transformative. Kuhn and Callahan celebrate the fact that “the digital humanities are not a unified field,” noting that “its relative murkiness is rich with potential.” They urge us to approach DH not in terms of more traditional, horizontal forms of interdisciplinarity, where resources are connected without substantial alteration to the structure of a discipline, but as a kind of vertical interdisciplinarity “where there is a rich layering in both method and practice of teaching and scholarship” that “poses challenges to the very discursive categories employed.” We have found their discussion useful in understanding the extraordinary collaborative energy that filled the room during the showcase presentations described above.

Our experience designing and teaching the institute has convinced us that without the right approach to DH pedagogy, the “relative murkiness” of DH is likely to be more confusing than enlivening, and the potential heralded by Kuhn and Callahan is unlikely to be realized. When we began planning our institute three years ago, we struggled with the task of introducing something so varied and multiform. How do you teach a field you can’t define? For us, the answer came in creating a framework of values that conveyed several core concerns of DH practitioners while highlighting DH’s relevance to the mission of our institution. While we settled on this framework early on, it was only in the classroom and over time that its power became clear. Among its key strengths is its minimalism. By avoiding the quagmire of defining DH, and emphasizing values that speak to both method and practice, teaching and scholarship, the CCPO framework taps into rather than squelching the lively diversity within DH. We see it as a means for harnessing creative potential rather than codifying or defining practice, for inspiring rather than limiting.

For those who might be interested in experimenting with similar or related ventures within their own institutions, we conclude with some practical advice. Teach DH around values rather than starting with particular methodologies or theories. Develop a values framework that speaks to the mission and specific concerns of your institution. Be tactical but have fun: revel in the spirit of play and inquisitiveness and open-ended experimentation that drives DH. Don’t obsess about technical competency. Don’t be scared off by the scale and technical sophistication of high-end projects. The principles and concerns of that work can likely be tapped into with fewer resources and less advanced technologies than you might expect. Sometimes your students will help you with the technology. Often you will need to work closely with technical experts on your campus, not simply as resources, but as co-creators. Take advantage of opportunities to collaborate with staff and faculty across the disciplines in different ways, experimenting and brainstorming in the new vocabulary of DH that accommodates insights and approaches from all fields. Be prepared for assignment ideas that reinvigorate or reconfigure curricular goals and maybe even generate research agendas that involve students and faculty across multiple years. A well-designed DH pedagogy has the potential to embrace the values that brought you to the humanities in the first place, and to cultivate the fresh insights and encounters that will help keep those values vital.