Early web commenters referred to the Internet as a primitive, lawless place like the “Wild West.” Plenty still needs to change to make certain parts of the web more civil and useful, but some aspect of the “Wild West” spirit is applicable to a discussion of student-directed learning. Too much civilization and society makes us compartmentalized and complacent. The West was a challenging place for European immigrants because it required an expansive sense of responsibility. You could no longer be just an apothecary or a cobbler. You had to provide for your own food and shelter from the resources around you; you had to decide just “what to do” with all this freedom.

Digital culture is having a similar effect on the practice of education, and that’s a good thing. Students have to own their learning more. They can’t just follow the dotted line on the ground that leads to their assignment, their grade, their degree.

Consider four core values for the classroom in general and the online classroom: show up, be curious, collaborate, and contribute. The online classroom is more student-directed in the sense that students are more “on their own” than they are in a traditional classroom. With more authors, contexts, and platforms to consider, digital media literacy insists that students filter, evaluate, and prioritize information with more critical proficiency than traditional students. Traditional students could trust the stability of the worksheet and the textbook. Digital education by its mere existence insists on more progressive practices for teachers and students. Digital culture has already started affecting dominant cultural epistemology by shifting some focus away from experts and giving it to participants.

Students in the digital environment, whether in a hybrid or fully online classroom, carry more responsibility for their own progress. To succeed, they have to monitor their own progress more directly, engage with the insights of their peers, and ponder the external relevance of their work. A revolution is growing online that takes this trend to an extreme — digital citizens are building educational communities without institutions. “Learning” no longer means, or needs to mean, “going to school.” It can just mean developing good observation and critical thinking skills.

What this means for the online classroom is twofold: 1. We recognize and communicate the shift from a follow-the-leader framework to a framework in which the authority is more equally distributed between teacher and students. 2. We have to model this new approach to learning in our classrooms (whether analog or digital). Students might be happy to see the culture of experts and talking heads dissolve, but if they want to be part of the revolution then they have to be ready to share the work that the experts used to do. For example, we might have students blogging publicly instead of submitting their work to the instructor as a one-to-one transaction. In this move, students become content creators, instead of content consumers — creators of their own educations instead of consumers — textbook creators instead of consumers.

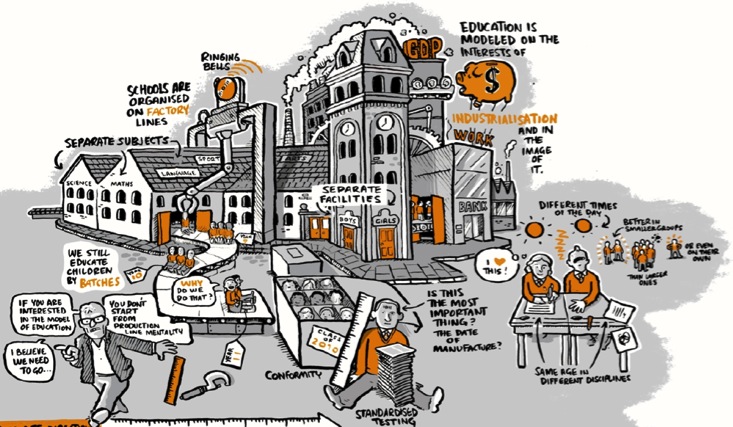

Traditional classrooms, the ones inspired by factories, create ideal students who follow instructions well. (“Changing Education Paradigms,” a video from RSA animate, offers a cogent argument for this shift in thinking about education). The web and digital culture create ideal citizens who investigate things “just because.” These students reach for Wikipedia or Google Maps on their iPhones to get immediate clarification when they need help. Our online classrooms should harness this educational holster mentality. Don’t understand something? Ask the class, email a group of professionals, call the company, interview your grandmother. And this is the beauty of digital and critical pedagogy; when it’s done right, it connects us to each other and to the world.