This sentence — this one right here — is the first sentence I’ve written in two months that wasn’t co-authored in a Google Doc. It’s the first sentence, outside of e-mails and tweets and notes I’ve written to myself, that has my name (and only my name) on both its front and back ends — the first sentence I can look at and say with certainty, “I wrote that entire thing without help and without anyone else watching it get written.”

My Hybrid Pedagogy co-editor (Pete Rorabaugh) and I hatched the plan for this journal in a Google Doc, and we’ve since written 29,316 words in that document. Before the end of 2012, we will likely produce the equivalent of a lengthy academic book. We contribute ideas synchronously and asynchronously, writing together at specific times and taking turns in the document on our own. Our collaboration runs so deep that single sentences are usually co-composed, our cursors occasionally blinking in unison within a single word. While I still recognize the texture of my own language and the idiosyncratic turns of my writerly voice, I don’t take ownership of my own writing the way I once did. And it isn’t just that I’m no longer attached to the sentences I write when collaborating; rather, I find myself more and more unattached to (but not detached from) the writing I do no matter the circumstance.

Words do work. The most meaningful work I’ve done in the last year (with Pete and with my inimitable colleagues Rebekah Sheldon and Charlotte Frost) has brought my words into conversation with the words of a co-author. For me, doing important work has begun to depend on collaboration, a transaction that demands more than just the simple transfer of words and ideas from a writer to a page and then to a reader. My ideas are better when they are coterminous on the page (and produced together) with the ideas of my sources, my peers, and also my students.

As part of our collaboration, Pete and I have instituted what we call the 1000 Word Challenge, in which we compose and edit 1000 words together in 1 hour inside our Google Doc. We enter the collaborative space with a loose topic that we’ve only minimally researched. Many of the articles we’ve published on Hybrid Pedagogy have been drafted during these sessions.

Recently, I asked my Hypertext and Electronic Literature students to engage with me in a similar experiment, which had 10 of us taking exactly 1 hour to co-write a single polished 500-word essay in a Google Doc in response to the question, “Why Does Literature Need Computers?” What resulted was a brilliant, coordinated effort as the various tasks that go into the creation of an essay were delegated evenly between the members of the group: a leader (while I participated, one of the stipulated rules was that I couldn’t be the leader), researchers, several people drafting paragraphs, an editor, etc. The goal of the experiment was less about product and more about process — about learning to navigate mass collaboration within a digital environment. (Click here for the prompt and the resulting essay.)

My own work with Google Docs has been inspired by several other projects that use the tool in novel ways. Howard Rheingold recently published a “Social Media Literacies” syllabus inspired by his book Net Smart (with versions for high school and college courses). At the top of the document, he invites viewers to “use, modify, and share” the course materials and even offers commenting and editing privileges to potential contributors. “The Adjunct Project,” organized by Josh Boldt, relies on hundreds of contributors to a Google Doc spreadsheet to assemble “data on treatment of contingent faculty” across the country. Finally, THATCamp organizers and participants have used Google Docs to collect and collaboratively annotate documents outlining work done during sessions. Many of these are announced on Twitter as the session is underway, allowing remote participants to eavesdrop on (and contribute directly to) the conversation.

A potential pitfall of this sort of work is a variation of the bystander effect, whereby participants will see a problem or gap in the document but assume someone else will fix it. The more collaborators involved, the more the effect is amplified. One solution is to delegate ownership of different parts of the process to each participant. While smaller scale collaborations (of 2 or 3) are simpler logistically, they still present certain challenges.

10 TIPS FOR NAVIGATING ONLINE COLLABORATION IN A GOOGLE DOC:

1. Think about the interface. The specific word processing software we use — the pen, paper, or keyboard — changes the nature of our writing. We write differently depending on our instrument, on whether we hold a keyboard in our lap on the couch or write with pen and paper while sitting upright at a desk. Before I write anything, I like to survey and experiment with my tools, to see how they influence my thinking and language. When we choose a tool, we’re making a creative choice, and it’s important not to take that choice for granted.

2. Embrace chaos. There is something slightly crazy about a shared writing space, especially when there are more than 2 contributing authors. A Google Doc can seem to write itself, a new digital ecosphere that bubbles with lively and chaotic energy. I’m frequently startled when I leave a Google Doc to realize that it will go on without me. If you haven’t collaborated within a Google Doc, start by choosing a low-stakes project and experiment. Don’t be surprised when weird and sometimes wondrous things begin to happen.

3. Carefully choose your writing partners. My first experience in a Google Doc was with someone I had only just met. It was less important that we had no experience of each other’s process and more important that we were both eager to try the experiment. In other words, don’t force anyone at gunpoint into a Google Doc.

4. Tailor your process. Most writers are used to working on their own. Respect your processes and approach the collaboration in a way that feels organic and natural. If it makes you nervous to have someone watching your words appear as they’re composed, take turns in the Google Doc, rather than writing synchronously. But don’t be afraid to take risks. Experiment and if something doesn’t work, change it.

5. Swap roles. Depending on my mood, I can approach a collaborative-writing session as an editor or as a content producer. I’ve been most productive when I’m working with someone with whom I can effortlessly swap these and other roles.

6. Don’t be shy. One of the most powerful features of Google Docs is the ability to review the revision history of a document (File > See Revision History). If something drastic happens in the document, you can always go back and track changes or restore an earlier version. So, don’t be afraid to finish each other’s sentences and to fight cursors a bit as you’re working. Some of the best sentences I’ve written are only half mine, and I can’t always tell which half is mine.

7. Use the chat feature. Use the chat function for meta discussion about the process. How is the writing proceeding? What larger issues are you seeing? When will you need a break? When will your next writing session be?

8. Make reflective comments. Use the comments feature (Insert > Comment) to suggest substantive changes or to ask content-related questions; however, sometimes I’ll write these kinds of comments right in the document itself (and delete them after they’ve been seen). There are no rules or hierarchies regarding what sort of meta-commentary can go where.

9. Write with a deadline. There is much discussion underway about the gamification of learning. I also encourage, both in my classroom and with my peers, the gamification of writing. Set arbitrary parameters, like 1000 words in 1 hour, and raise the stakes: with my hypertext students, for example, I cheekily warned that I’d be tweeting a link to our co-written document once the hour was up.

10. Share. Google Docs aren’t, by their nature, designed to be private, so let others (beyond just your co-authors) into the process. Err on the side of giving viewers too much permission rather than not enough. If you give editing rights to contributors and they muck up your document, you can always use File > See Revision History to restore a previous version.

In the spirit of that last tip, here’s a link to the Google Doc in which I wrote this article. Consider it unfinished, and modify tips, add tips, fill in the list of resources below, etc. And, a question to consider in the comments: How have digital environments for collaboration changed the ways you work, write, and teach?

Some additional resources:

1. Document Sharing and Markup by Pete Rorabaugh

2. Google Drive Wants to Sync Your Stuff by Brian Croxall

3. Google Docs and Collaboration in the Classroom by George Williams

4. Experiments in Mass Collaboration by Pete Rorabaugh and Jesse Stommel

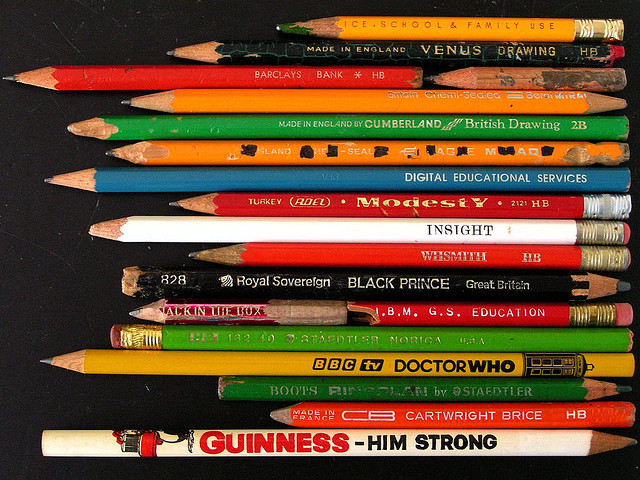

[Photo by jovike]