It’s time to confront our bias against open sources and redefine how our students research in digital environments. We should both allow them to use the research sites that are most handy, i.e., those openly available on the internet, and teach them how to effectively mine, evaluate, synthesize, and use the information contained within those sites.

Good research is an art form and good researchers use a variety of techniques. The art of research is knowing how and when to use the various tools and techniques in concert. While students rarely approach research as an art, never have the tools of research been more readily available to them. The trick is to teach them how to use those tools with finesse.

In a recent Chronicle of Higher Education article, Dan Berrett cites a study conducted by the Citation Project that suggests that the First Year Composition course is not doing a good job of teaching students how to effectively research and use sources:

A presentation of the project’s initial findings . . . told a disheartening story: that students rarely look past the first three pages of the sources they cite and often stitch together a patchwork of text, with little evidence that they absorb their sources’ content along the way.

While the majority of students in the study selected materials from resources that are generally considered reliable, they demonstrated a lack of ability to evaluate the reliability of individual sources and to use their research findings in a nuanced way. The study’s investigators point to digital media as one potential culprit in the supposed decline in critical reading skills, as it encourages “grazing texts” and skimming rather than reading deeply. But good researchers graze and skim all of the time; the difference is that they know how to use grazing and skimming to locate sources with potential that need to be read more carefully.

The Citation Project study addresses many of the same issues that have been raised within larger debates regarding open internet sources. In her article “Building Good Search Skills: What Students Need to Know,” Tasha Bergson-Michelson argues that the false dichotomy between paywalled sources and open sources ignores the question that we should really be addressing:

“What do students really need to know about online search to do it well?” As long as we’re not talking about this question, we’re essentially ignoring the subtleties of Web search rather than teaching students how to do it expertly. . . . Regardless of the vehicle — fee database or free search engines — we owe it to our students to teach them to search well.

As Howard Rheingold points out in Net Smart: How to Thrive Online, “The mindful use of digital media doesn’t come automatically.” In contrasting the power held by those who know how to filter and use digital information proactively with those who passively consume open content, Rheingold paints a bleak vision of the dystopia that awaits those who do not learn how to control and critically decipher the information cyberculture of the 21st century. Increasingly, promoting Rheingold’s ideal of media literacy is our job as educators and net citizens.

In lauding sources that must be accessed via an academic library, whether in-house or through a subscription database, we’re ignoring the fact that very few of our students will remain academics once they graduate. If one of our goals is to teach them how to be better informed and more involved citizens, then perhaps we need to shift our focus away from restricted sources of information to the kinds of open sources that will allow them to engage in global and community issues more fully.

Many scholars use social media to build professional learning networks, sharing sources with one another, as well as promoting their own work. Professional conference-goers create backchannels on Twitter, quoting presenters and linking to cited sources, and sometimes even crowdsource Google Docs of sessions. As these experts become more open to using social media to communicate, endorse, and share information, their information becomes more accessible to those outside their domain. This openness can, in many ways, be a good thing, but it should not be blithely dismissed as the answer to students’ research prayers, for it allows a flow of information that is overwhelming, even for the experts trying to curate it. Recognizing the need to teach students how to manage and mine this flow of invaluable information, David Korfhage has created a how-to series for doing just that (“Using Social Media for Student Research”: Part 1 & Part 2).

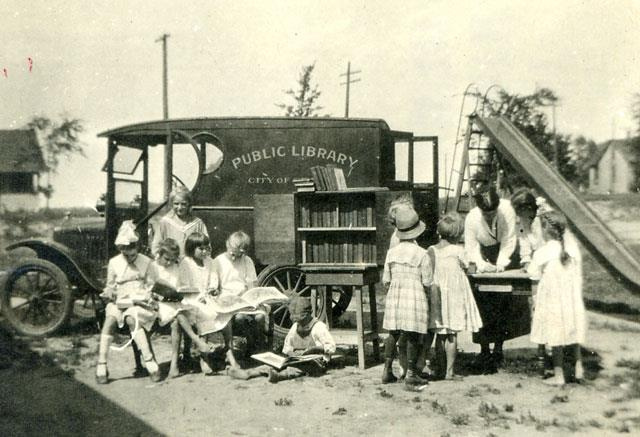

Just as library cataloging systems developed in the wake of the invention of the printing press, tools currently exist for filtering and curating the infinite flow of information streaming across the various social media channels. Like the bookmobiles of the past, sites like Storify allow users to find, select, and package small bundles of information and deliver them back out into their information community for use and commentary. Such a tool can be useful in monitoring and providing feedback on the sources that students select during their research and how deeply they are thinking about what the sources say and how the various voices connect with one another. Storify, for example, allows users to collate and organize Web content, then publish their “stories” on-site and share/embed them in other social media sites, such as blogs, for reader commentary. This opens up students’ sources for critique from peers and their instructor (and, potentially, others outside the class). Students can also add commentary on the content via text boxes within the “story,” providing space for them to annotate their sources in the same way they would a traditional annotated bibliography. (For an introduction to Storify, including steps and tips for getting started and examples of Storify projects, see “How to Storify. What to Storify”.)

This past term I experimented with requiring my second semester FYC students to not only use open internet sources to locate information for their literary analyses, but to use Storify to create their annotated bibliographies. Storify provides direct browsing in Google, Twitter, YouTube, Flickr, and Facebook, so I asked students to stay within these open resources for their initial research and encouraged them to use sources from as many of these browsing options as they thought relevant. As the term progressed, students learned how to use filtered resources, such as Google Scholar, and used the “embed URL” tab to integrate these sources into their “stories.” They had to aggregate their sources and arrange them into a logical order, as well as provide a summary of each source’s significance within the context of their analysis.

After posting these Storify artifacts to their blogs, students then had to read and comment on those of their peers. I encouraged students to focus their comments on the relevancy and reliability of their peers’ sources, as well as offer feedback on their annotations. I also read and commented on their “stories” as soon as possible after they were due so that students would have ample time to conduct more research or revise their “stories” if needed before beginning to work on their analyses.

Encouraging students to use Storify to create their annotated bibliographies was effective on multiple levels; most significantly, their peers and I were able to monitor and provide immediate formative feedback on the relevancy and reliability of their sources. I was also able to identify overarching issues that students were encountering in locating, interpreting, and engaging with their sources, and address those issues in mini-research lessons during class. As I integrated these lessons and as students reviewed and discussed each other’s annotated bibliographies, they began to locate and Storify more robust and reliable sources and to engage with them in more purposeful ways. Below is an example of one student’s bibliography and an excerpt of our discussion about it. This example demonstrates a rather nuanced approach to the various types of sources, both textual and visual, available to the student and how locating and dialoguing with such sources prompted him to make connections he might never have made had I restricted him to the library databases.