Everyone is a teacher, whether on purpose or not.

I never wanted to be. In pre-school, I remember vividly telling all of my sticky and sandy friends on the playground that I was going to be a veterinarian and play with cats all day. In grade school, I was to be an artist and a writer. I was going to paint and write about the beautiful and ugly world around me. In middle school, I wrote fiction in the corner of the classroom and avoided the other kids, and got all of my assignments done early so I could work on whatever short story or novel I was crafting. High school was not as straightforward. I wanted to be a writer, a surgeon, an artist, a journalist, a world traveler, a singer. Never not once did I think of becoming an educator. In fact, when people asked if I had ever considered teaching, I would stick out my tongue at them and shake my head.

That is not to say that I disliked my teachers; it was quite the opposite. For the most part, I have been incredibly fortunate to have teachers who care. Those are the teachers I choose to remember; not my fifth grade teacher who made us teach ourselves math, nor my seventh grade science teacher who enjoyed barking orders at us.

No. Instead, I remember Mr. Jason in third and fourth grade, standing on top of the tables and singing “Another One Bites the Dust” by Queen as he threw a dried up Expo marker across the room into the trash can. If he missed, we would groan. If he got it in, we would all start singing “We Are the Champions” at the top of our lungs. I smile when I think about Mr. Todd in sixth grade, assigned as my mentor, who allowed me to stay home most days and sent me my homework, because my parents were getting divorced and I had developed a mental health disorder. He told me it was okay to feel and it was okay to be sad and reflect. As a sophomore in high school, a lot of people hated our English teacher, but I respected him like no other. He was not fond of students taking bathroom breaks or dressing in pajamas, but he valued literature and taught me the importance of a beautifully written novel or short story; he preached about the importance of recognizing the history within literature.

College did not go as expected. I had a plan: finish with my undergraduate degree in Biomedical Sciences, get into medical school, complete a surgical residency, and then maybe I would get married and have kids.

Instead, I spent my freshman year at the University of South Florida, where most of my professors were alright, but not memorable. Then, because I fell in love hard and fast and unexpectedly, I got married at nineteen and moved away. I tried online school for one semester and deeply disliked it, then transferred to another university in Florida for awhile, and not long after, my husband got orders for us to be stationed in Virginia.

I would have to transfer again. I was frustrated, even though I knew this would be the last time I would have to do so. After all of the uncertainty and change, I dropped the Biomedical Science degree aspiration and had decided on an English degree. I always dreamed of a career in the medical field, but math and science were not my strong suit, and I did not have the discipline back then to make that goal my reality. On top of that, I would have to retake classes when credits did not transfer over—some for the third time. Nothing had gone my way, academically, and I was ready to snatch my diploma and never look back. I was not excited about new classes, or meeting new people, or moving somewhere so far from home. More than anything, I craved consistency; I’d had enough change in too little time.

My sister, an academic, who has connections with educators across the country, made a post on Facebook asking if anyone she knew taught at the University of Mary Washington. She knew I was not excited, and she wanted me to be happy to be a student again. That is when a man named Jesse Stommel commented on her post and told her he was teaching at UMW and would be glad to meet with me.

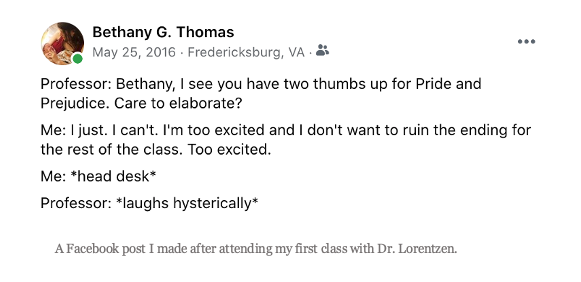

I was not able to take a class with Jesse for at least a semester, and so I went into my first class in the Summer semester as a complete newbie: A Floridian who had never attended a liberal arts college, a Navy wife whose husband was gone for training, an overall anxious mess. I left my linguistics class feeling completely and utterly incompetent. My Jane Austen class that same afternoon did not make me feel any better. I got into my Kia Soul in the parking lot and bawled my eyes out. My sister had not lied when she told me that classes at UMW would be harder. Before then, I had no idea what the Norton Anthology was. Or where the library was on campus. My professor used huge words that I had never heard before. I do not think I’d ever felt so helpless and out of place in my life.

On my first paper in my Jane Austen class, I received a D+/C-. I had never gotten worse than a C+ on a paper in all my life. My soul was crushed. Was I not a decent writer? Was I stupid? Should I just drop out? I swallowed my pride and went to see the professor, Dr. Lorentzen, which was something I never did. I was too shy and my ego tended to be too big for constructive criticism. I sat down in his cozy little office and looked at all of the books on the shelves: Austen, Dickens, the Brontës. I liked my professor a lot, but he scared the hell out of me. His blue eyes looked at me, and I could tell he felt bad about my grade. He said something along the lines of: “I can tell you’re a good writer, but your organization needs work.” Dr. Lorentzen, who had at that time been my greatest fear, became my favorite professor in my college career that day. I finally had a teacher who challenged me, but also connected with me and took the time to know me. I ended up studying abroad in England with him and taking another one of his classes. Throughout the rest of my undergraduate career, I visited him frequently. I met with him before moving back to Florida so that he could meet my newborn daughter, and made a friend for life the day that I cowardly walked into his office to talk about my bad grade.

I did not meet Jesse until months after I started at UMW when I took his Introduction to Cinema Studies class. We were Facebook friends, so I knew a little about him, but not a lot. Instead of the usual ice breakers that almost all professors insist on making students do at the beginning of the semester, Jesse had us pair up and talk about what Hogwarts houses we belonged in. When he called on me and my partner, my partner told Jesse that I was a Slytherin. Jesse sneered at me from the front of the room and said “Of course you are!” I clapped back with, “Says a Hufflepuff!” I liked him instantly.

After the class ended, Jesse surprised me by offering me a student aide position at the Division of Teaching and Learning Technologies, where he was the director. Jesse had made me feel even more passionate about film within his class, and I was excited to work in an office with him, but I had absolutely no idea what I would be doing or what kind of office it was. What did “Division of Teaching and Learning Technologies” even mean?

Within my first month, I cannot tell you how many times I had to look up the definition of pedagogy. I was honestly scared to say it out loud for fear of mispronunciation. It became increasingly apparent that I was surrounded by educators—educators who cared deeply and were passionate about teaching and their students. I felt very out of place.

Working at the Division of Teaching and Learning Technologies led to a lot of things I never thought would happen, especially as an undergraduate student: I became a part of Digital Pedagogy Lab, where I engaged with teachers from all over about learning and how students feel in the modern classroom; I attended keynotes on digital pedagogy; joined in open, pedagogical discussions with professors of UMW and voiced my opinions in a safe space where teachers and students could talk simply and openly on a very real level; and eventually I led a workshop, "Bringing Imagination to Teaching" at Digital Pedagogy Lab, where I taught the importance of going back to our childhood roots and exploring our imaginations as both students and teachers.

And yet, I still did not, and still do not, want to be a teacher.

A year after I graduated from UMW, I started to look for jobs back in my hometown of Tallahassee, Florida. My husband was about to get out of the service, and we had a newborn. I’d need to be the “breadwinner” after we moved so that he could go to school. My mother sent me a few state jobs, and jobs at Florida State University. She sent me one job that caught my eye, but I felt it was too good to be true: the Writing Specialist at the College of Law. The job description noted that they needed someone to help law students with their grammar and writing skills, and that I would assist legal writing professors and teach workshops.

I was used to working with professors, but the idea of leading workshops terrified me. After all, I was not a teacher. I never wanted to be a teacher. So, when I was called in for an interview, I was overwhelmed. I went to Jesse in defeat when I accepted the job offer and said, “I guess you got what you wanted. I’m going to be a teacher after all.” He grinned and I rolled my eyes. He had been trying to get me to be a teacher for almost as long as I’d known him.

As the move got closer, and my first day loomed over me, I talked myself into it:

You’ve been surrounded by educators for the last few years, and you love most of them.

Maybe you’re meant to do this.

It won’t be so bad to teach in front of students. It’s fine. You will be fine.

Literally all of your friends and mentors are teachers. You should be enjoying this.

So, I began my teaching job. I talked myself into it. I even applied to a Creative Writing MFA program. But deep down, I knew this was not right. Something was wrong. It took the pandemic for me to stay home and reflect on what I wanted as a career, and it did not take me long to figure out that teaching was not what my soul needed. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, I did not look forward to going to work—I especially did not look forward to the days where I taught workshops. After the pandemic, when the law school went remote, I breathed a deep breath of relief with the knowledge that I did not have to teach for awhile.

The truth was, I hated it. I dreaded standing up in front of a group of students and hearing myself talk. I did not want to explain the same things over and over. I was bored when making teaching plans, and answering the same questions week in and week out. I grew increasingly anxious of being the center of the room and the discussion. Though I have many wonderful memories of the classroom, none of them involve me in the center of the room, near a white board, or in front of a projector screen.

And that’s why I respect teachers so much. They enjoy meeting with their students, and talking to them, and lecturing, and giving constructive criticism, and watching their students succeed. They enjoy getting up in front of a class and having complex and sometimes difficult conversations with the same set of students for months, just to be rewarded with a brand new batch come the next season. They spend countless minutes reading and viewing students’ work, and though they might complain about the hours, unlike myself, they tend to do it happily.

I have been told that I am a wonderful teacher. I have been told that I explain comma splices and passive voice better than most. I loved seeing my students’ eyes light up when the connection finally hit. I loved helping them and connecting with them.

Yet I still dislike teaching.

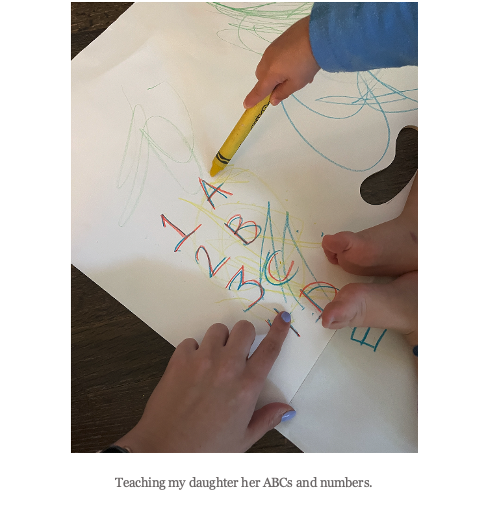

We are all teachers, even when we do not want to be. I primarily teach in less recognizable ways: I teach my toddler how to take deep breaths when she is frustrated; I teach my husband to walk away from a project when it becomes too overwhelming; I taught myself how to take care of plants; I taught my mother what panic disorder means and feels like; I taught my stepmother what it means to have a daughter.

I prefer teaching people how to take care of pets, or how to read their tarot cards. I prefer sitting down with my curious daughter and laughing with her as we sound out simple words with difficult letters. I prefer teaching to those I already know, and learning from them in return. I do not crave the classroom. I do not aspire to be the person who changes their students lives and impacts them deeply.

Not everyone wants to be a teacher. But whether in a classroom, on the playground, in the kitchen, in the car, or just at work, we are all teachers to one another day in and day out.

My aunt taught me how to make fried okra just like my Grandma Dot used to make. My best friend taught me how to trust in true friendship. My eldest sister taught me how to stand up for myself, and my other sister taught me the beauty in laughter. My father taught me to cherish music in the darkest moments of life, even if you have to stay up all night to do so. My mother taught me how to be a healer. My stepmother taught me how to love myself and others without restraint. My husband taught me to breathe and take things as they come. My daughter teaches me something new every single day—most recently, how to sit down and just be.

I was not meant to be a formal educator. Those close to me have the passion for it that I never will, and I love watching them grow and glow with pride as they talk about their students and lessons and all that they are researching or writing. Educators made me who I am now: a confident young woman who follows her heart and sticks up for herself. Educators showed me my true passions in life: writing, healthcare, mental health awareness, animals, family.

I never wanted to be a teacher, and now that I have left my teaching job, my circumstances have changed yet again. Now, I help teachers and trainers with their curriculum instead of being the woman at the front of the class. But despite no longer being a "formal" educator, I will go on teaching stuff, like how put on shoes or how to wind down after a long day when life gets to be a little too much.

As I go forward into my next unpredictable chapter, I know I will lean and depend on the teachers whose classes I enroll in as I chase after the medical career I have always dreamed of.

It took me becoming a teacher in order for me to understand how I learn; I learn better because of the teacher inside of me that I never wanted but have learned to give thanks to.

I’m grateful for teachers. Those in the classroom and those outside of it. I’m grateful for the journey, because even though I never wanted to be, I am glad I was a teacher, even if only for a little while.