This reflective and speculative cross-genre provocation aims to reveal emergent patterns in the context of education in the Anthropocene by assembling broken bits of thought and practice, theory and story, prose and poetry, a teacher’s voices and students’ voices. Such fragments might be imagined as wrack—pieces of driftwood and other floating object detritus discovered along the rising tide line or, in a time of climate chaos, at a glacier’s retreating edges. Wrack is what remains of damage, disaster, devastation—embodied and psychological. Wracked by glacial loss, sea-level rise, extreme weather events, unpredictable shifts in climatic patterns. Fires in California. Freezes in Texas. Hurricanes in Puerto Rico. The more-than-human world stretched to a breaking point. Our minds and bodies also, excessively strained and stretched in new directions by grief, anxiety, and the guilt of complicity in systems of extraction, consumption, and colonialism: systems that create wrack, that create wreckage.

Yet can wrack also nourish? An important part of shoreline ecosystems, wrack can provide habitat and nutrients to various species and communities. Invertebrates like kelp flies and isopods (“roly polies”) rely on the organic materials washed up by the waves, and shorebirds like sanderlings and flycatchers feast on those tiny creatures. During the breeding season, such birds also rely on the wrack to shelter newly-hatched chicks. And yet many human communities, particularly those who have become divorced from the land, too often ignore the wrack, seeing it not as nourishing but as nuisance: something to be avoided (yes, it’s smelly!) or cleaned up to provide more recreational, privatized space for the few. We are entering a future of more and more wrack. Will we acknowledge wrack as a shared commons? Or strive to control it under the isolating logic of neoliberalism? Will we walk the wrack line alone or together?

Philosopher of science Bruno Latour calls on us to “attend to the wreckage.” In what ways does environmental education in a time of climate chaos equally require an attention to the wreckage? Students and teachers alike might work together to develop the skills of salvaging, might also join together their own emotional wrack. As an environmental educator, tracing the wrack of my work and life has been a practice in gathering attention, noticing the ways in which wrack itself can be a teacher. So, what follows is an experiment in attending, collecting, assembling, leaning into–—and learning into—the wrackage.

“One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds.” —Aldo Leopold

Renowned twentieth-century ecologist and environmental writer Aldo Leopold was wrong about many things, including most notably his xenophobic perspectives on immigration. He was wrong, too, about ecological education.

Yes, an ecological education is an education in living with wounds. But we don’t live alone.

Saturday night I am sitting in a room called the Commons with a group of students who are taking part in a residential environmental education program. Some students are relaxing on couches and playing scrabble, arguing over spellings and counting triple word scores. Another student is teaching themselves how to play guitar—they have been working on it since the fall term when they took up the practice as part of a Thoreau-inspired experiment in deliberate living. Three other students are in the kitchen area, using locally-sourced ingredients to bake a cake that they are then going to decorate with white and blue frosting in the shapes of polar bears and icebergs. They plan to submit the cake to an environmental edible art contest. A few other students are sitting at the dining table, laptops open and catching up on their work—writing essays about cli-fi (climate change fiction) for their Environmental Literature class, running R programming scripts for Ecology class, and reading essays by Leopold and Robin Wall Kimmerer for Environmental Ethics. Surrounded by such music, art, and youthful conviviality, I am considering what it means to teach in a time of climate chaos.

Students often identify education as the “silver bullet” to solve climate change, economic inequality, systemic racism, and a host of other problems of the Anthropocene (or as French political scientist Françoise Vergès calls it, the “racial capitalocene”). If only we could educate more people, they say, especially more young people, everything would be possible. For years, I dismissed these and other similar claims as naïve. I reasoned that these students’ views had been shaped over years of adults telling them that it was their generation who would fix everything, who would clean up after the mistakes of those who came before them, who would save the world. I made sure to disabuse them of the notion that education, and specifically environmental education, could be a panacea. No, I told them. More or better education will not substantively remake the world, or at least, not quickly enough and not to the extent that the reality of climate chaos demands. Moreover, historically and still today the educational system is complicit with the ideologies and structures of extractivism, speciesism, settler colonialism, and white supremacy.

Why did I tell them all this? To complicate, to challenge, to deepen their thinking. To draw their attention to the ways in which education can unwittingly perpetuate an unjust and unsustainable status quo. But in bluntly explaining to the students that environmental education was not a solution, I did not honor their desire to make sense of their work and role in the world. I did not honor their deep commitment to education in general and to their own educational journeys. My desire to complicate and challenge obscured the fact that students wanted desperately to believe in the power of education. They wanted to contribute to that larger human project of bettering the world through learning. They had conviction.

In 2017 in Southeast Iceland, local guides discovered two enormous 3,000-year-old birch tree stumps that had been revealed by the retreating Breiðamerkurjökull glacier. The island was once covered in beautifully tall birch and beech forests in the valleys that graded to birch and willow scrub toward the coast and to willow tundra at high elevations. Around approximately 500 BCE, the climate cooled and glaciers began to advance, destroying parts of the forests; then, in the centuries of 800-900 CE Norse settlers cut down most of the remaining trees to use for building material, livestock fodder, and most importantly, for charcoal, which was needed to smelt iron and make tools. At the time of human settlement, forests covered 40% of Iceland. Today, that number is 2%.

Unexpected assemblages at the terminus: human, ice, rock, tree. Grief and wonder. Brokenness and beauty. Two birch stumps now making their way to a museum in Reykjavík where a 100-meter-long artificial ice cave, constructed from 350 tons of snow from Icelandic mountains and kept cold with massive refrigerators, will one day be the only glacier left.

Media and technology theorist Steven Jackson’s framework of “broken world thinking” asks us to acknowledge the “limits and fragility of the worlds we inhabit” (14). Such thinking initiates what Jackson describes as an ethics of maintenance and repair, which, as he puts it, “highlights actors, sites, and moments that have been absented or silenced” (15). Adapting such a framework to education, and environmental education specifically, would aim to help students cultivate the skills and resilience necessary for working with brokenness—their own and the world’s. It would focus on care and repair rather than on innovation, development, progress, and learning management, thus serving as antidote to the neoliberalization of education, which treats students’ emotions, bodies, and imaginations as sacrifice zones. Moreover, such an approach to education would make space for teachers to acknowledge their own brokenness. Teaching for a broken world. Broken world teaching. Working with the wrack.

“Beech bark disease (BBD) is a scale insect-fungus complex that has caused the decline and death of afflicted beech trees. This disease has become a common feature in North American forest landscapes. Resistance to BBD is at the level of the beech scale (Cryptococcus fagisuga). Beech scale attack predisposes the tree to subsequent infection by Neonectria fungi. The impact of this tree disease has been shown to be significant, particularly in beech dominated forests. Scale-free trees (resistant to BBD) have been reported to range from only 1% to 3% in infested stands, with estimates ranging from 80–95% for overall infestation (for all beech within the current North American range). In addition to BBD, overall beech health will be directly impacted by climate change, if one specifically considers the expected fluctuations in precipitation leading to both drought periods and flooding. Beech is particularly sensitive to both extremes and is less resilient than other broadleaf tree species” – Christopher Alexander Stephanson and Natalie Ribarik Coe, “Impacts of Beech Bark Disease and Climate Change on American Beech”

“Instructions on how to get to my tree friend: If you go on the hiking trail at the back of the building and head straight for the bridge, you will eventually see a tall, elegant, and grand American Beech. You will know it when you see it, or rather hear it. For if there is any wind, the Beech will be playing music. You can touch the trunk and leaves while standing on the bridge. Don’t forget to bring it a gift, say thank you, and play along. Don’t forget to listen.” – Junyang Sun, “Beech Tree Symphony”

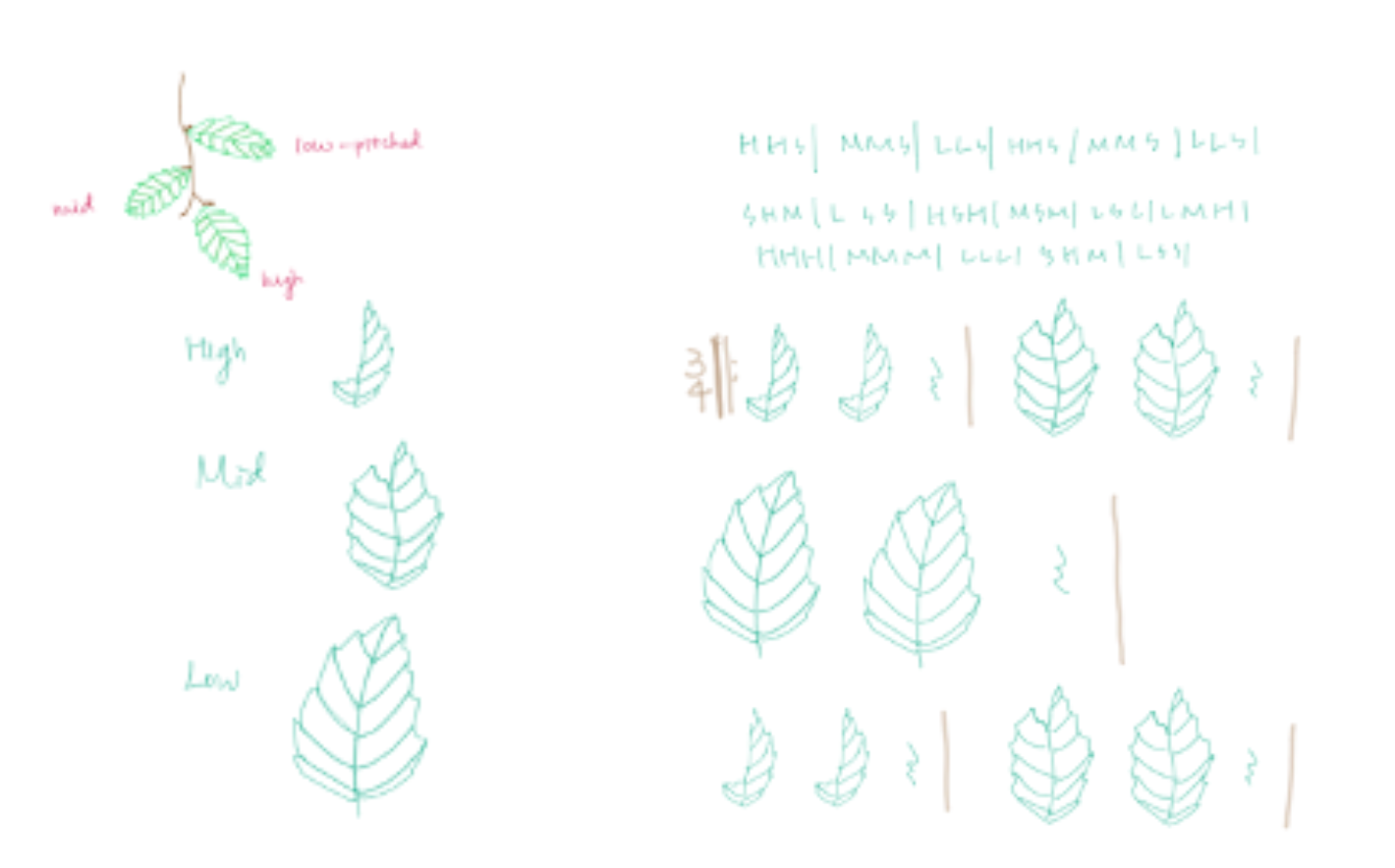

Befriending a tree, a practice in cross-species collaboration and aesthetic practice. A selection of musical notation from “A Beech Tree Symphony,” included with permission by Junyang Sun.

In 2017, the Heartland Institute began sending climate change denial textbooks to 200,000 public school science teachers around the country. Without going into too much detail or giving too much space to this particular example of educational wreckage, it is important to note how these textbooks deploy a veneer of “objectivity” while misconstruing data and advancing logical fallacies so as to undermine the scientific consensus on climate change. They shatter climate science into a jumble of broken and individuated parts. A denial not just of scientific reality, but the reality of the world’s interconnection.

How can teachers counter the forces of denial and destruction that infiltrate not just the political and social life of a nation but also its education system? It is not enough to educate students by exposing them to clear data and sound arguments. Since there exists not just an information deficit but a deficit in shared practice, environmental education needs, as Bruno Latour suggests, to “reorient to the terrestrial”. If environmental education is going to contribute to the broader social-ecological project of rebuilding a multispecies commons, teachers must open paths for students to traverse back into material relationship with the earth.

Witness what there is to repair. Gather up the broken parts. Practice convivial cohabitation with the Beech trees.

A writing prompt from the game The Thing From the Future:

Imagine a transformed future two generations from now.

Imagine a school in that future.

You feel

excited

delighted

a sense of wellbeing.

You have ten minutes.

Imagine together.

Play.

Student response #1 to prompt : “A school that takes place in a forest. In fact, the school is a forest and it is part of an entirely new education system, one that gives students opportunities to follow their specific passions while cross-pollinating with human and more-than-human others. They learn how to survive, and thrive, in a time of climate change. To do this, students will then learn how to communicate effectively with each other, with other human cultures, and with other species.”

I am standing with a group of high school students, my faculty co-leader, and a local guide on the summit of Ok, a dormant shield volcano in the highlands of west Iceland. Blasted by unpredictable winds, we huddle close for warmth and struggle to keep balance on the ice and rock. We are standing next to the remains of Okjökull, the first glacier in Iceland to have died because of anthropogenic climate change. To be a glacier, the ice must be thick enough to sink and move under its own weight. Okjökull is the first Icelandic glacier to lose its title. In the distance, we see the towering white walls and jagged seracs of Langjökull, Geitlandsjökull, and Þórisjökull. They are much larger than Okjökull was, but they too will soon be gone. There are 269 glaciers in Iceland. In 200 years, except for a few tiny and mostly inaccessible ice caps, they will all be gone.

The magnitude of this change can overwhelm. Some students talk among themselves of what they want to do when they return to school: get involved in campus environmental groups, write about the experience, tell others what they saw. Others take photos with their phone cameras (no service here, so they’ll have to post images to social media later), trying to document their experience of “last chance tourism.” Others still sit alone and in silence, eating trail mix and granola bars to keep warm. In the face of unimaginable loss, keeping up conviction can take a great deal of energy.

Elsewhere on this island we have walked stretches of black sand beach strewn with melting ice diamonds each unique in cut and color yet each consigned to the same quick death beneath an endless summer sky that—though beautiful—has been weaponized by climate change; we have crawled through blue tunnels of a glacier’s heart ice; we have watched water rush from glacier to sea across outwash plains in great road-eating flows; we have imagined our home places—Hong Kong, Gloucester, Santa Barbara, Miami—flooded, burning, gone. We have grieved.

Student response #2 to prompt: “A global school based on a model of experiential learning. There are no grades, and you can pick a location to travel to and learn about every school year. This allows for the world to unite and give future generations a global education and the appreciation for exploring new and different places, especially those that are impacted most by climate change.”

I dislike the words “wellness” and “self-care.” In my years as a teacher, I have come to associate them with institutional initiatives that include “wellness days,” lunchtime yoga classes, stress balls, and meditation apps.

When not coupled with an emphasis on community care, such initiatives do little to address the structural issues leading to the mental health problems affecting young people today: the deep-rooted racism, sexism, and xenophobia embedded into the institutions and systems that shape their lives; the white supremacist violence and toxic masculinity at the root of school violence; the increasing economic inequality; the social isolation worsened by the Covid-19 pandemic; and all of these things amplified by climate change, the threat multiplier. In this time of such interlocking traumas and chronic grief, caretaking could be one of the most important tasks of educators and educational institutions. Students often realize this better than their teachers. They feel the un-wellness, and some students, such as students who identify as BIPOC, students who identify as non-binary, students with disabilities, and first-generation college students, feel it more acutely than others. This is true of climate grief as well.

Several years ago, a group of students I worked with organized a student-run community wellness session that they called “Climate Tea Time.” To slow down and snatch back time for shared delight and comfort, students gathered to bake scones, drink tea (sustainably sourced), and discuss their futures in the context of climate change. As the organizers explained in their rationale:

There are limited opportunities on campus for us to engage in meaningful and honest conversations about this issue that will shape our futures. Climate change is not only an environmental issue but also a mental health one. Feelings of sadness, despair, and frustration are all growing among young people. Teenagers who live with “climate grief” need opportunities to care for themselves with relaxing tea and supportive peers and slowly ease into hard discussions about the environmental crisis… This brief but hopefully long-lasting gathering will not only bring more people to care but also comfort those who feel frustrated living in a time of climate change. #climateteatime

In running “Climate Tea Time,” these student leaders aimed to cultivate community, hospitality, and conviviality, and create a welcoming respite in the daily storm of being young in a time of climate chaos. Of course, such events might be more difficult now during Covid-19. Yet given how the pandemic has both exposed and worsened the broken systems that perpetuate injustice, we (educators and students alike) are in greater need of convivial connection, community care, and an ethic of repair. We have much salvaging to do together, and there’s no reason we can’t do that over a cup of tea.

[ A set of alternative learning outcomes (not sanctioned by your institution) ]

By the end of this course you will be able to:

courageously imagine alternatives

to capitalism, colonialism, speciesism, ableism, and white supremacist patriarchy

shake things up

step in the muck

dwell with the world’s beauty in all its paradox and unknowability

walk out of the prison house of dualistic thinking

collaborate generously—

don’t critique, compose!

love the world

harder still, accept the fact that the world loves you

attend to the delights of daily life

bear witness to the world’s wounds

attend to and care for the brokenness of your peers and your own

take the path of vulnerability

retreat when you need to

enter the quiet space

that grief requires

reconnect

hopelessly entwine yourself with other species, critters

attend to their brokenness too

act with conviction

but know that such action will

never be enough

that such action will

never complete the task

rest.

Student response #3 to prompt: “A building that defies the current imagination, and even defies the constraints of physics, considering that it exists both in the clouds and underwater, because of sea level rise. The school functions as a base camp for classes, which consist of traveling bands of students and teachers, roaming the world to learn about everything and anything they can. There’s no homework, per say, but students learn what they want, volunteering their time and effort into helping communities learn subjects like sustainable cooking and aquaculture and environmental activism. The school itself has the largest library of any educational institution, and all classrooms—if you can even call them rooms—are filled with stones and plants and other animals, who are all also the teachers.”

Why do students come to class every morning, whether in-person, hybrid, or remote? Why do they go above and beyond the parameters of every assignment, searching out ways to raise the stakes of their own learning? Why do they choose this program to begin with? Why do they desperately want to imagine and enact a better world for themselves and their peers?

I am thinking differently about environmental education in a time of climate chaos.

I am thinking that such education can be powerful.

These students who learn, write, and daily break bread together call me into a greater conviction about the power of education, the power of teachers, and the power of my own choices in the classroom (and outside it). Their conviction, their sincerity, their hope, is a gift that I must learn to reciprocate.

In a time of climate chaos, hope is not something to have, to own. Hope is a gift we give to one another. No, not quite that. Hope is the giving.

Back in the Commons a student working on their essay shares with me a recent epiphany they had after reading Rebecca Solnit’s Paradise Built in Hell: That climate change disempowers people. But also in many cases, and paradoxically, can re-empower them, by bringing them together, as collectives of care and understanding.

No, I think, that’s too easy.

But yes, I think, that’s about right.

In a collective we can begin to make things right.

That can repair what is broken.

The room smells of vanilla and red velvet batter. The student with the guitar has discovered how to play the opening measures of The Beatles’ “Blackbird.” In the vernal pools behind the building, wood frogs are laying their eggs. Through the open window we can hear the chorus of their cackling.

This feeling is not quite love and it’s not quite community. It may be a feeling of overwhelming abundance. That there are so many people, so many beings, who are in it together, who are, to echo Donna Haraway, staying together with the trouble.

An ecological education is an education in living with the wounds. But we don’t live alone.

For Okjökull*

“Even a wounded world is feeding us. Even a wounded world holds us, giving us moments of wonder and joy. I choose joy over despair. Not because I have my head in the sand, but because joy is what the earth gives me daily and I must return the gift.” –Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass

If we could we would give you a gift

maybe something of ice something

of stone and water and light

ptarmigan and moss and arctic fox

something like that which you have given us:

your glacial shine.

If we could we would love you like we love each other:

hungrily.

If we could we would traverse this island

carrying nothing on our backs

speaking your praises

sharing your songs

telling stories

of how you used to make

your own weather.

We have walked through artificial ice tunnels.

We have studied maps and timelines of loss

already here and more soon arriving.

We have looked through the bluest ice

reached out to touch a million tiny snowflakes

holding hands.

Rituals of grief, they say, are not

for the dead

but the living.

We have swallowed your heart.

We listen for the beat.

*Spoken by teachers and students at the summit of Ok, where Okjökull, now a dead ice field, once grew. A gift, given too late.