It is only from a place of extreme privilege that someone is able to shelter themselves from politics, as many must face the consequences of the political system in everything that they do. This is especially true of educational institutions, in and through which structural inequality is systemic, unfairly impacting students, faculty, and staff of color. In my 2017 article for Hybrid Pedagogy, I outlined an approach to teaching highly politicized topics through service learning, but more specifically I explained how I taught a course on the issues of citizenship and what I would do differently in the future. Now, in 2020, the week after one of the most contentious elections in recent history, I find myself reflecting on the evolution of this project, and how my approach to bringing politics into the classroom has changed. Our country is deeply divided, and as a result of—or perhaps at the root of—that chasm there are certain “hot button” topics that are sure to ignite controversy. It may seem easier to avoid these topics, or navigate course conversations away from these debates. However, in reimagining my courses, I have tried to meet the challenge of discussing political topics transparently and aggressively to frame a space for students to engage in the much needed discourse of social justice through the lens of rhetorical empathy.

As Lisa Blankenship writes in Changing the Subject, “from its beginning, empathy has signified an immersion in an Other’s experience through verbal and visual artistic expression. This element of an immersive experience that results in an emotional response, as well as the associations of empathy with altruism and social justice, possibly explains its continued linguistic cachet over terms such as pity and sympathy” (p. 5). In my courses we study the stories of American immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers, and I try to move the discussion away from the feelings of sympathy at best, or indifference at worst, to a place of altruism. I say “courses,” because at the time of my first article this work was isolated to my Digital Publishing (200-level) class, but now has become central to my Introduction to Literature (100-level) and Grant Writing (300-level) classes as well. Teaching this content at three different levels to a variety of audiences has helped me hone what is essential to the success of the course, and that starts with language. I find many students are reticent to participate in conversations about controversial topics because they do not know the appropriate language to use, and they do not want to mark themselves as in opposition to anyone else in the class. In fact, in their reflection essays students lament that they wish they would have spoken up more and express similar sentiments of struggling to find their voice. Based on this feedback and my research on declining empathy rates, I started experimenting with both analog and digital tools to immerse students in the rhetoric surrounding citizenship in the United States.

Start with the Personal

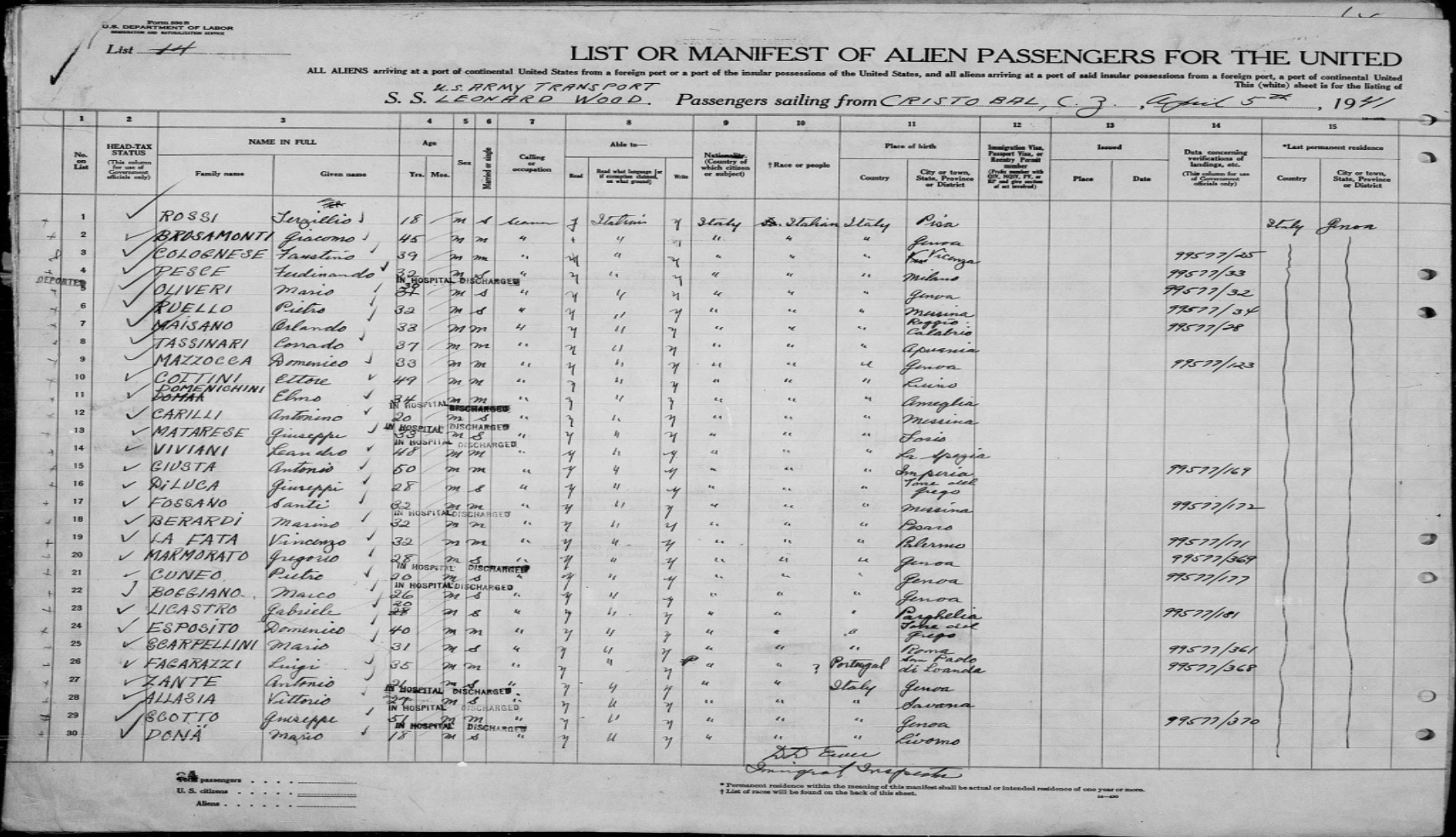

After too many years avoiding revealing any personal information to my students, I realized that in order to establish my position on the topic of immigration, I needed to share my story. I start from a place of vulnerability, in hope that this openness will inspire bravery. In the first week of class, I search the free Ellis Island Passenger Search for the name of my grandfather, Gabriele Licastro, and go through the process of reading clues to fill in the details of my family history.

By asking questions of the passenger manifest provided on the site—What kind of ship were they on? Why is everyone on board male? Why is everyone on board marked as a “seaman”? Did you notice how many passengers were hospitalized?—we are able to draw some solid conclusions: My grandfather was a prisoner of war, brought over on a military transport in 1941 with a group of captured members of the Italian military. I then share that my grandfather was put in a labor camp, where he survived by cooking for the American officers, and when eventually released, found employment as a chef in Cleveland, Ohio. Students experience the act of historical research, but through the lens of empathizing with a real human, their professor, who has inherited this generational trauma.

I don’t ask students to reciprocate with their immigration stories; each student determines for themself whether to disclose personal information. Instead, I follow with a low-stakes creative-writing project inspired by npr’s “Where I’m From” series. The results are simply gorgeous. Students write short poems about their families, home towns, traditions, fears, regrets, pain, and joy. I also encourage each student to record themselves reading their work to share alongside their poem. Especially when we were forced to be fully remote in March 2020, these glimpses of vulnerability brought a sense of community and caring to the sudden distance. Perhaps even more so than in the face-to-face classroom, inviting the personal into a virtual learning space breaks down the walls of academic discourse and helps students find their voice.

Interrogate the Public

After looking inward, my classes turn to representations of citizenship in popular media sources. I ask students to find sources from the last six months that focus on issues faced by immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. I encourage students to find articles from sources they are likely to read outside of class. The goal here is to capture a wide variety of sources to analyze and compare together. To my surprise, students rarely duplicate articles, which suggests the class is diverse enough to retrieve different search results, or have different filter bubbles, which are issues that we discuss in class together.

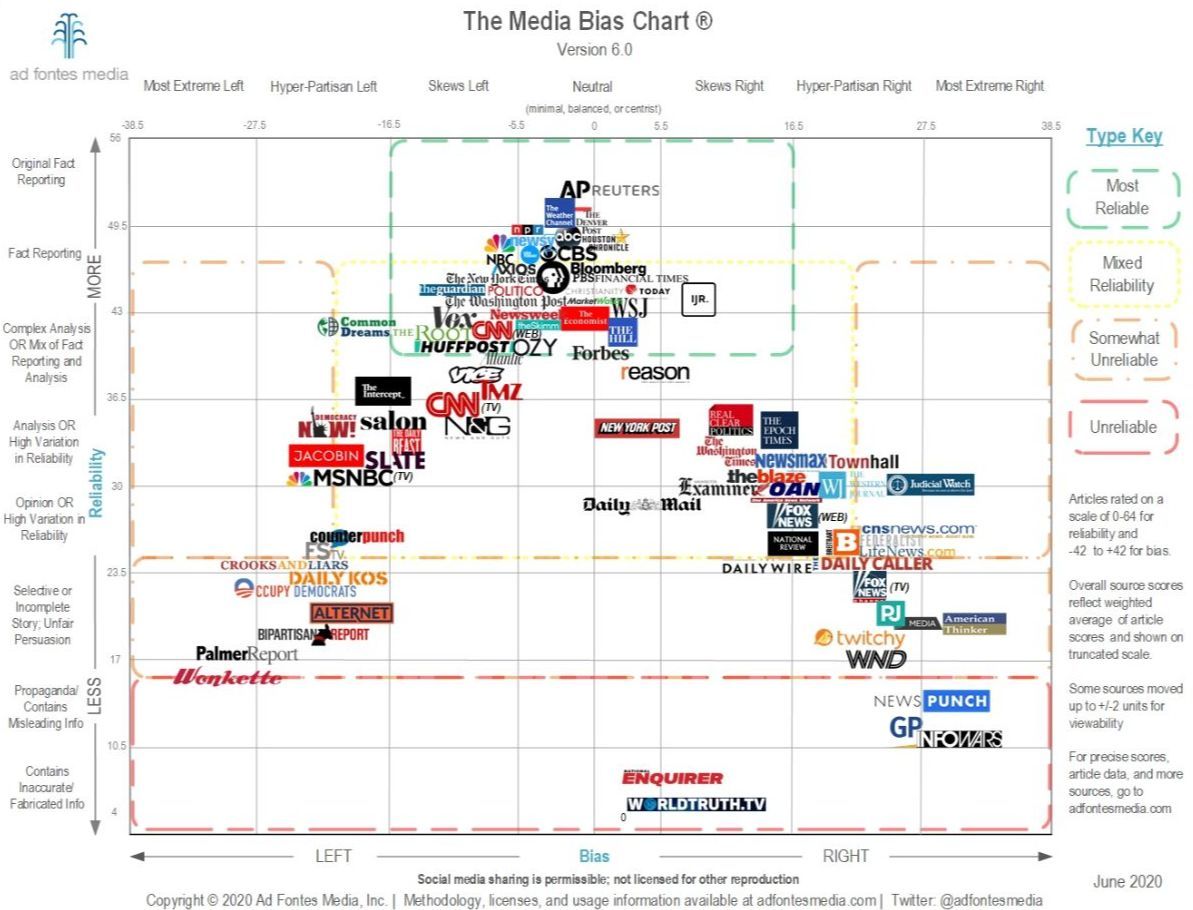

Then, in collaboration with Sara Godbee, the subject librarian embedded in my courses, we guide the students on a lesson in evaluating bias and identifying loaded rhetoric in news publications. This activity could be easily adapted for any topical issue, and can be done remotely or in person. Students locate the publication they selected on the widely-seen “Media Bias Chart”, and then label their article as left-, center-, or right-leaning.

Once the articles are labeled, we create a “gallery walk” (shamelessly borrowed from Dominique Zino, Associate Professor of English at LaGuardia Community College), by posting the articles around the room—which can be done virtually via a discussion board or blog. Students identify and plot words that convey urgency or bias from the left/center/right, using polling software online (which could be done with sticky notes in person) to track word frequency. We use the visualizations to draw conclusions about language used in journalistic reporting. We discuss how terms like “crisis” appear across both sides of the political spectrum, but labels such as “alien” and “victim” are polarized. Inevitably, there are surprising results that contradict our expectations, allowing both the students and myself to re-evaluate our assumptions. Thinking through why we expected certain terms to be associated with the left or right helps us uncover our own political bias.

The process is repeated with articles from academic journals, with the timeframe expanded to the last five years to accommodate scholarly publishing timelines, which demonstrates how language changes over time and in different disciplinary contexts. In a short reflection assignment, students consider how language is welded politically—even in scholarly publishing—and how this exercise prepared them to enter a specific discourse community. The exercise prepares them to distinguish between—and enter into—both the academic and service communities. I put pressure on students to consider why it is important to go beyond the concept of what is “politically correct” and instead investigate what terms they feel comfortable using as an individual now that they have examined the rhetorical strategies of multiple sources.

Finding Truth in Fiction

Perhaps no one better contextualizes the problem with language than Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. In my 2017 article, I concluded that the course would be better served by integrating fiction to provide students with more diverse narratives to connect to, in particular, Adichie’s 2013 novel, Americanah. That has proven undeniably true. I’ve introduced this novel into two separate courses, alongside her 2009 ted Talk on “The Danger of a Single Story,” pairing it with a rotating selection of scholarship, poetry, and short stories that fit the needs of that year and student population. For example, in my Fall 2020 Introduction to Literature course, which serves as the only Intercultural Knowledge Competency course in the university, I’ve used a combination of the following resources:

- I show the videos for “Immigrants” from The Hamilton Mixtapes performed by K’naan and “This is America” by Childish Gambino paired with the annotated lyrics via genius.com. These sources serve as an introduction to close reading visual and textual representations of immigrant narratives.

- We collaboratively annotate poetry by Langston Hughes, Jimmy Santiago Baca, and Hai-Dang Phan using social annotation software, specifically hypothes.is.

- We consider short stories by Carmen Maria Macado and the graphic novels of Kate Evans, and I ask students to analyze small sections of the text they find provoking.

- I bring in Virtual Reality (VR) immersions such as “Limbo”, “The Displaced”, and “Clouds Over Sidra”, as well as critiques of the medium from Janet Murray, Liz Losh, and Lisa Nakamura.

In each text, we find moments of familiarity, points of connection that help us identify with the characters, but then also points of departure that highlight our differences and make the texts challenging. As we traverse these tensions, the complexity of empathy is apparent; we have a hard time understanding those we see as Other. While all of these texts are difficult for students to navigate, the conversations are rich and full of the kind of exploration needed to reframe representation as historical, cultural, and institutional.

The results are some of the most poignant student work I’ve witnessed in my ten-year career as an educator. Nothing seems to resonate as strongly with students as Adichie. Therefore, I’ve made her novel the anchor text for my “remix” midterm project in which students select one character and tell their story in a new medium. In groups, students create podcasts, video games, comics, or VR experiences that require them to research the political and social issues at work in the narrative thread they chose. By collaborating together, and choosing roles that best fit their strengths, students break down the work into manageable chunks and help refine the overall concept to an achievable vision. Peer review sessions and conferences with me also aid in avoiding pitfalls and troubleshooting technical difficulties.

One group, compelled by a slew of articles about black students being discriminated against at school because of their hair styles, made a podcast episode titled “Neither Hair Nor There” in which they interviewed two of the female characters about their experiences trying to find products to take care of their natural Nigerian hair in America, and interspersed references to the articles by way of asking the characters to reflect on the prejudice they faced. They ended the podcast post with real resources to help black women find legal language to advocate for themselves as well as natural products to maintain a variety of hair textures.

Another group created a stealth-mode VR simulation set in London which traced Obinze’s plight of trying to remain unseen as an illegal immigrant after his student visa expired. The player has to wear a variety of masks as he assumes different identities through borrowed or stolen documentation. The goal is to remain unseen while still working, traveling on public transportation, buying food, and entering into an arranged marriage for the purposes of gaining citizenship. This method allows the player to witness the unending stress and anxiety faced by millions of undocumented workers around the world.

And yet another group used Twitch to design a decision-based game in which the player decides whether or not to engage in illegal activities while trying to survive as a legal Nigerian immigrant in the United States. The sheer number of branches their decision tree had—and the images they chose to embed throughout—impressed me, but the act of forcing the player to face these decisions was the most powerful part of this game. The game offers players a view into the authentic tragic and unjust trade offs our society sets before immigrants.

Blankenship defines empathy as “both a conscious, deliberate attempt to understand the Other and the emotions that can result from such attempts—often subconscious, though culturally influenced” (p. 7). As I hope you can see, these projects require a great deal of academic rigor while making space for emotional and personal connection to the material. Based on Collaborativism from Linda Harasim, this constructivist approach to pedagogy emphasizes peer-to-peer learning, allowing those who may feel marginalized or underrepresented in a classroom to be in a position to lead or share expertise. Classmates share their diverse experiences and perspectives, stimulating difficult conversations but also innovative problem solving. Of course, some groups stumble, projects stall, and individuals disagree, but those efforts are valued even if the final product is not perfect. The point is to experiment with the unknown and apply what they have learned to make something new. The goal is to better understand the experience of asylum seekers through the lens of rhetorical empathy.

Serving the Community

Rhetorical empathy is particularly important in my service-learning courses, where students work directly with asylum seekers. Understanding the language students use to address and describe our clients ameliorates the apprehension in these encounters. Students enter the immersion with the tools needed to be thoughtful and empathetic in their interactions with the staff, volunteers, and asylum seekers themselves. As I learned from my previous experiences engaging in service-learning work, it is important to have multiple community partners in case situations arise that make the collaboration impossible to complete. Therefore, I now invite three or four organizations to present to the class, and students choose which they feel passionate about serving. This allows students to match their interests to the coursework, and gives each group a clear motivation for the final project.

The final project varies based on the course objectives. The 300-level students draft real grants to funding agencies, the 200-level students create digital products for the organizations to distribute, and the 100-level courses submit small internal proposals for one-time events or projects. Consistently students articulate the value of having real clients for their final project, expressing that the high stakes of providing resources for those in need motivated them to excel. They are also able to explain that this final project enables them to apply what they had learned throughout the semester to a tangible outcome outside the limitations of the classroom, giving them an opportunity to synthesize a variety of materials and make use of the content for the greater good. These connections are exactly what I hope to achieve as an educator. Working from Adiche’s prompting, students share examples of their lived experience and develop trust and authority as they cross cultural boundaries, empathizing with teammates as they work to build empathy for the client.

In critiques of empathy, many suggest that because empathy is an emotion, it is fleeting (see, for example, Against Empathy from Paul Bloom). By connecting the immersive narratives students experience to the application of those lessons in the service they provide to our community partners, the empathic response moves from emotion to action—empathy, then, is a catalyst. It is precisely this movement that makes the argument from Blankenship so compelling to me and negates the common critiques of empathy.

Conclusion

As dedicated professors, after we work on a course so diligently, and thoughtfully, sometimes for years, we hope the effort has an impact. We read through the glowing reviews of our students and accept the praise of our colleagues with satisfaction. However, there are also times when we must face the unexpected results, the comments that, despite our very best intentions, prove that there is more work to be done. In spring 2020, my 100-level Intercultural Knowledge Competency course received the kind of student evaluations we all long to read—except one. One that stated, “I wish it broadened the demographics of immigrants besides African Americans.” That anonymous comment gutted me. After three years of carefully crafting a beautifully diverse set of voices to uplift my students and make space for sharing and connection, I was met with the blatant realization that one course, one teacher, one program, would never be enough. I cannot cover all of the concerns, represent all of the voices, and influence everyone’s perceptions in one semester.

This moment of personal failure was later compounded by the hopelessness felt nationally by educators whose intellectual, emotional, and physical labor was erased by a political policy. The oxymoronic Executive Order on Combating Race and Sex Stereotyping resulted in the closure and cancellation of diversity programs at universities across the country. How can we cultivate empathy in our classrooms when the national dialogue contradicts our efforts through a much louder, much more powerful platform?

My answer for you is the same philosophy I use in my classrooms: collaboration and community. We must find strength in numbers, because one classroom, one teacher, one program will never be enough. But if we commit to making every syllabus, every curriculum, and every college more diverse, our platform will be amplified. And further, if we connect those learning objectives to service learning, and engage in outreach with our students, the message will be too loud to drown out.