Embracing our subjectivity as teachers can be tricky; I’ve written several times about how complex it is when teachers make the choice to be non-neutral. I’ve admitted it could be seen as indoctrinating. But believe me: pretending to be objective or neutral only hides our subjectivity, it does not actually remove it. For example, it takes sensitivity and caution to not make male students feel silenced during discussions of gender, but it’s also impossible for a woman to pretend to be neutral in this context. This explicit non-neutrality is a characteristic of critical pedagogy. As Davies and Barnett suggest, the “critique” inherent in critical pedagogy is focused on uncovering what might be hidden behind claims or arguments, which is different from more traditional notions of critical thinking that focus on identifying weaknesses in arguments in some objective way. Critical pedagogy and critical approaches to curriculum are creative and subjective processes, inherently influenced by the teacher’s (and learner’s) lenses of looking at the world. This is so different from traditional notions of critical thinking, which is why I think it sometimes takes a while to express it and discuss it with others.

I was giving an introductory workshop to undergrads about critical pedagogy the other day. A bit ambitious for one hour, I know, but I wanted them to look at critical thinking in a different way. To be able to think about criticality as a way of questioning oppression from multiple lenses of gender, race, postcolonialism, social class, etc. One of the simple activities I did was to encourage them to question the hidden messages behind some fairy tales/Disney movies. Things like the message behind “Beauty and the Beast” (It’s ok to be ugly — but only if you’re the guy — and in the end, you have to turn into a handsome prince. I prefer Shrek on this one!) and Aladdin (Not only does princess Jasmine fall for a thief and not a Robin Hood even, but the imagery used to represent the Middle East is slightly offensive, and the way Jasmine is dressed…it’s more like how Arabs used to dress their slaves, not their royalty.). Things like that.

So when I reached a discussion of Egyptian school curriculum, and I asked, “what’s wrong with…?” a supervisor of this group interrupted me and said, “but that’s not a neutral question”, to which I responded, “I am not trying to be neutral. Critical pedagogy is explicitly value-laden.” And it is. I was asking a leading question in the sense of leading participants to consider that something is ‘wrong’, but it’s not leading in the sense of necessarily expecting a particular answer as the ‘right’ one. Raising consciousness is sometimes about asking, “What is wrong with…?” from a social justice perspective.

I discussed my belief that social justice is not one monolithic clear thing, that our histories and contexts shape our perspectives, which in turn color our judgment of what constitutes social justice. I talked about that briefly in my workshop; I didn’t use the term “positionality” but alluded to it.

Which brings me to research. I was once having a discussion with a colleague about research. She was saying, “we need to try to be objective”, and I responded, “no, we need to make our biases and subjectivities explicit”. She looked at me and said, “we’re saying the same thing”.

I beg to differ.

There is a difference between perceiving objectivity and neutrality as “higher” values to strive for, and recognizing that we cannot reach them. That’s my friend. By contrast, I argue that subjectivity is the human condition. Everything else that attempts to be objective or neutral is pretense. It is inauthentic. It is not even something I strive towards.

What about providing statistics about learning? That’s not objective either. Behind those statistics is research that contained questions that were decided upon by particular people. Those choices of questions to ask, correlations to look for, which ones to report, and how to represent and interpret them? Layers upon layers of subjectivity hidden behind an illusion of objectivity.

Interpretive and critical research, on the other hand, clarifies the researcher’s subjectivity. In fact, it makes subjectivity central to what the research presents and represents. It offers readers the agency to judge for themselves which parts of the research to take or leave. As Jon Nixon (an educator who has influenced my thinking greatly) writes, “all understanding is always already interpretation” and “the interpreter is always already part of what is being interpreted” (33) and as such “all understanding necessarily involves an element of self-understanding” (34). This is central to interpretive approaches to research, and even more so for approaches such as autoethnography that make the researcher a central subject of research. I have recently completed co-writing two articles reporting on collaborative autoethnographic research; to report on our experiences, we had to be explicit about how we felt about the topic of our research in order for the reader to recognize our lens and positionality; we did not attempt to convince the reader that we were attempting to provide an objective perspective. Objectivity is beside the point, because none of us goes into an experience objectively: we are always ourselves. Or at least, some dimension of ourselves.

When teaching, putting a number on a grade doesn’t make things more objective. Creating a rubric doesn’t make things more objective, either. There are values behind our choices of what to give grades for and how much weight we give them. And that’s ok. Subjectivity is the human condition. Let’s reconcile ourselves with it. Or better yet, embrace it.

Embracing subjectivity does not justify an “anything goes” mentality. William Perry’s levels of intellectual development have an intermediate stage called “multiplicity” where people lose the absolutist mindset of depending on authority. But it has a more advanced stage called “contextual relativism” which implies that what is more or less true depends on the context.

Speaking of grades, I do not mean to suggest that students can just each give themselves a grade and consider it good enough (though you could try that, I guess), but it also means that our authority as teachers is not the absolute and only valid judgment of the student’s learning. It implies a more complex negotiation of what it means for a student to have learned: a dialogical, emergent understanding that is not based on pre-defined rubrics or arbitrary numbers and letters. It also suggests an openness to questioning what it means when we emphasize certain things in a grade, or when we try to “order” students in terms of who performed better or worse.

People sometimes think I am being an “easy grader” when all I am doing is making sure all my students learn something worthwhile, and I choose to “reward” them for doing it, because most of them end up doing it, and learning, because I give them enough chances to do so. My goal is not to filter better performance from worse; it’s to help students learn. As long as I reach an understanding with my students about what we all consider to be learning in my class, I’m happy (thrilled, even) when they all do, even though it might mean something different for each student. Why wouldn’t I be?

Kris Shaffer describes the difference between grading student work looking for errors and focusing on technical details, as opposed to looking at student work holistically, and accounting for the student as a whole person. He explains how this mindset shift made him focus less on how to mark down a student, and instead, how to help them make their work better. This includes considering ways in which what we ask of our students may be inconvenient or unsuitable to their needs or circumstances or even interests.

Embracing subjectivity entails opening ourselves to questioning and evolution. It means recognizing that our truths might be different from other people’s truths. In pedagogy, this is what Palmer refers to as the teacher’s openness to listening to students’ truths empathetically. It implies that as teachers, learners and researchers, we need to practice what Keith Hamon has called “assertive humility”:

“No one’s frame can claim an objective, transcendent, privileged status against which all other frames may be judged or assessed.”

The implications for pedagogy include recognizing how curricular choices are political; Freire points out that every content choice we make needs to be questioned in terms of “who chooses the content…in favor of whom, against whom, in favor of what, against what.” We need to ask these questions about our teaching process, about our assessment choices. Lee Skallerup Bessette recently shared a story of opening herself to new ways of assessing student learning, and her realization that assessment could go wrong and inadvertently punish our more “audacious” students.

Palmer talks about how our academic culture suppresses subjectivity, and by doing so, distances students from their own inner realities. He calls on us as teachers and learners to reclaim our hearts and to address each other’s souls, an idea also suggested by bell hooks. To do so, we need to stop thinking of external reality as more valuable than subjectivity, to stop treating subjectivity as a barrier to overcome. Let’s embrace it as the human condition, treat ourselves and our students as whole, absolutely subjective, human beings, and see where that takes us.

Maha Bali is a Hybrid Pedagogy featured columnist.

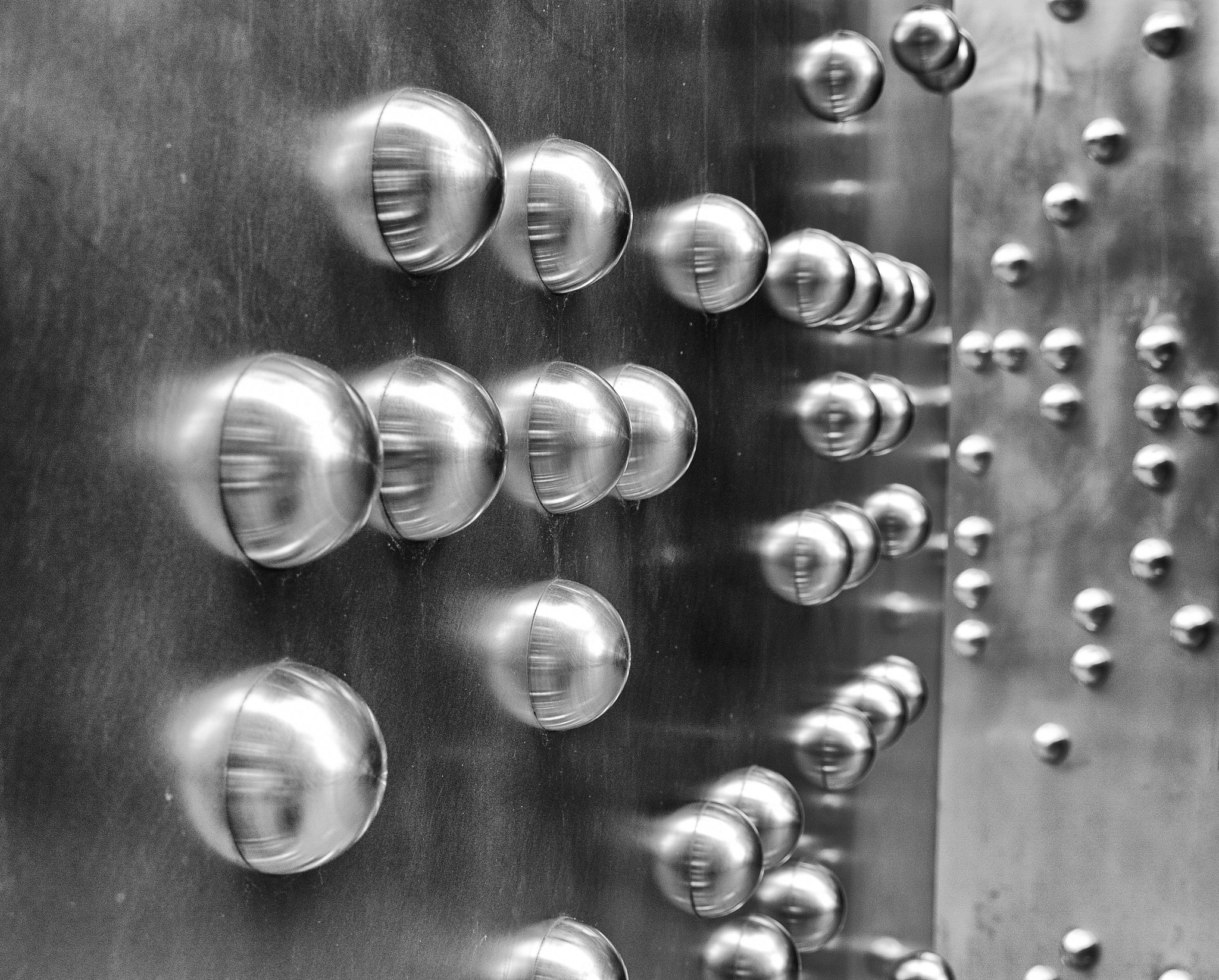

[Photo, “Skin of Words“, by Emre licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.]