Traditional college students of today are completely mediated. They can tweet, text, and post to Instagram all day long; they swim through a sea of media, and are savvy with an array of technologies; they use phones that are smarter than the computers of just a few years ago. Students are continuously, and rapidly, improving on basic computer skills and often work with the computer intuitively to perform tasks and to solve problems when they get stuck. When students come together in a computer classroom, they bring with them a great variety of experiences and skills. Some students can navigate any task brilliantly at lightning speed, some get the same results at slower speeds, and some need more instruction for developing skills they may not have had the opportunity to practice previously. In my experience, this variety opens up spaces filled with possibilities for learning.

Finding out more about where students are when they enter the classroom, meeting them there, and then working with them to move beyond basic forms of communication and consumption into thinking more deeply about hyper-media, social media, the media industry, technology, and other cultural topics can now be endeavors for instructors in the computer classroom. Critical pedagogy emphasizes participation, engagement, and collaboration so that students become active producers and critics, and are not simply passive consumers ingesting course content. Bringing this philosophy into the computer classroom further opens the space for critical and thoughtful conversation about culture to happen naturally, and in which critique is often extended beyond surface commentary. This combination of physical space, technology, and engaged pedagogy can also foster another effect of working in the computer classroom, and that is the organic way in which community-building happens.

Classrooms on college campuses are often not designed to foster engaged teaching and learning, but instead to be utilitarian meeting spaces open to a wide variety of groups and purposes. The challenges for instructors in these institutional spaces can be great. But with a little creative thinking, a basic, or even thoughtfully designed computer classroom can become a hybrid, pedagogical space where students learn from each other, work together, and create community, while also interacting critically with media, technology, and contemporary culture.

For any class that I teach, I hope for a room in which the table or desks can move around so we can sit in a circle, or students can move into groups, creating spaces that lend toward conversation. In the best-designed computer classrooms, a large table for working with books and paper and having face-to face conversation is in the middle of the room; and computers sit on tables around the perimeter, facing the outer walls. Students sit next to each other at computers, or turn completely around, with their backs to the computers, to talk as a large group around the table. They can also move their chairs around and work in groups. Mike Palmquist and others have been writing about this kind of classroom since the 1990s, and I started teaching in this kind of space in the early 2000s. Especially in introductory level classes, this setup offers greater accessibility to writing, the Internet (as a tool and resource), conversation, and impromptu collaboration which can lead to thoughtful discussion and engagement. In this kind of classroom, I also plan multiple activities over any particular class period, and find that it has become easier to incorporate elements of reading, thinking, discussion, writing and revision into single class periods. Multimodal interactions also help students to practice skills in areas where they excel, or to learn from others who have different sets of skills. And since working with technology often includes inevitable technical issues, these can also be good learning opportunities. The well-designed computer classroom encourages students to cooperate and work together as needs arise; they help each other with technical issues; and they work together to read and comprehend written texts.

Although I have taught upper-level courses in which students designed web pages and discussed “the essay” as a hypertextual space, in any course my main goals include extensive practice in conversation and collaboration, reading, writing, and critical thinking, which, in introductory courses, often means less literal time and energy spent with computer technologies. Of course, the media and technology are still always “in the room” and we engage more fluidly with these as content (through discussion of issues) as well as tools we can use.

In a recent class, for example, we talked about social media after reading the article from The Onion, “MySpace Outage Leaves Millions Friendless.” We considered rhetorical context and the difference between parody and real news, and how the fake news was presenting a cultural critique. The students offered their own critique of the use of social media among their peers by explaining the differences between Facebook and Twitter. Because everyone uses Twitter now, keeping up with the barrage of Tweets among one’s peers can be exhausting and overwhelming; however, as some students claim, one can’t really opt out of this kind of social participation. This led naturally into a conversation topic often at the heart of my classes: the relationship between the “individual” and “society,” and our role as citizens in this complex, consumption-oriented, global world.

I want to engage students in a model of agency in which they as users also become producers and participants in the classroom, and in the world. As technology is changing the way we think about audience/user participation, we can extend this to also think about the changing role and practice of citizenship. After Anne Frances Wysocki, we can consider individual agency in terms of the materiality and use of media technologies. In this respect, users have more material access to production and participation, as we see a move away from models of passive consumption. There is no longer a simple notion that some people are producers and some are consumers. The potential for individuals to engage to varying degrees as both producers and consumers — and the changing definitions of what these mean — seems greater and more complex. Consumers may not all be passive for example, but may engage in different ways even if they are not directly producing media content. As the authors propose in Spreadable Media,

“we should not assume that audience activities involving greater media production skills are necessarily more valuable and meaningful to other audience members or cultural producers than are acts of debate or collective interpretation” (154).

Participation may and should in fact extend beyond “making” media to include critical engagement in terms of “evaluation … critique, and recirculation” (154).

In a capitalist and commercial society, it may be impossible to change the larger structure of production and consumption, but in more local ways of reimagining this relationship — and in the computer classroom in particular — we can use the dynamics of critical new media practice more thoughtfully. At once giving students opportunities for agency, sociality, citizenship, and community-building, models for media production and engagement can be multifaceted. Working within this model in terms of course content and physical space, forms of production and consumption are potential means for different kinds of networked learning and critical practice. After Paulo Freire, this sort of pedagogy values processes of critical learning and participation over “banking” knowledge. And a critical pedagogy involves a more complex thought process about the relation between production and consumption, between the user and the technology. Or to pull Marshall McLuhan into the mix, we might consider the classroom itself as the medium that is the message; the classroom can be a model for this new, more engaged relationship between production and consumption, between creating and evaluating and critically participating in culture. The computer classroom — its physical space and the possibilities it offers for engagement — can be a “technology” for building this kind of community.

My pedagogy asks that students learn as much from each other as from any content that I might provide. At the school where I teach, in Dearborn, Michigan, the students represent an array of cultural, linguistic, religious, economic, and other backgrounds, and part of my responsibility as facilitator/teacher is to help students to feel comfortable sharing and talking with one another in the classroom. Maha Bali and Shyam Sharma write in “Bonds of Difference: Participation as Inclusion” that

“educators can and should strive for genuine attempts toward inclusion by not assuming the local to be universal, by inviting colleagues and other learners to participate on their own terms, and by developing a high sense of tolerance and openness about difference.”

Their article focuses on online technologies for global communication across borders, and although my classes don’t involve working via computer with students across the globe, I already have students representing the global, and the culturally diverse, in our physical classroom, so a consideration of tolerance and relevance is equally important. In any given semester, Jewish students sit next to Muslim students who sit next to African American students; they represent the spectrum of gender diversity; some are from small towns, and some are from the various neighborhoods in Detroit, each its own community within the larger city.

When we talk about public education, these students share their stories from the schools they attended in so many different places, and they argue about the problems in school districts around the state and compared to schools in other countries. Many come to class talking about current news stories like the events in Egypt, or the situation between the Ukraine and Russia in the Crimean Peninsula, or the problematic media representations of the group self-named “The Islamic State.” We read selections from Aristotle on Democracy, and Benazir Bhutto’s memoir, Reconciliation: Islam, Democracy, and the West. Lately we are discussing the shooting of Michael Brown in relation to historical events, and the use of social media for organizing social protest. Through the readings and conversation, students both engage in critical literacy practices — reading and analyzing texts on cultural and historical topics — and share ideas about social engagement and agency. Often, students are then able to examine their own experiences with the context of these larger cultural issues.

Student agency in this sense can become a resource for community building. Breaking through cultural assumptions, opening spaces for conversation and collaboration, and moving between modes of learning and practice in the classroom space offer students a model for agency, community, and participation in culture. Particularly because of my experiences teaching (often back-to-back classes) in both traditional and computer classrooms, I have come to think more deeply about engagement in the classroom space. Any classroom can be a space for community in which vocal and reserved students, producers and consumers, and students of various backgrounds and expertise can work together and learn from one another. But I have also witnessed how the space of the computer classroom can enhance the possibilities for this kind of pedagogy and interaction. Media and technology can aid and become part of this process, but these are only part of a larger complex of factors. Fostering engagement through writing, discussion, and digital media is a way to model community building, and helps to make students feel included, involved, and to have a voice in classroom discussion, and in relation to social issues. And these kinds of practices can, as one might imagine, move beyond the classroom and into the larger world.

Hybrid Pedagogy uses an open collaborative peer review process. This piece was reviewed by Adam Heidebrink-Bruno, Chris Friend, and Sean Michael Morris.

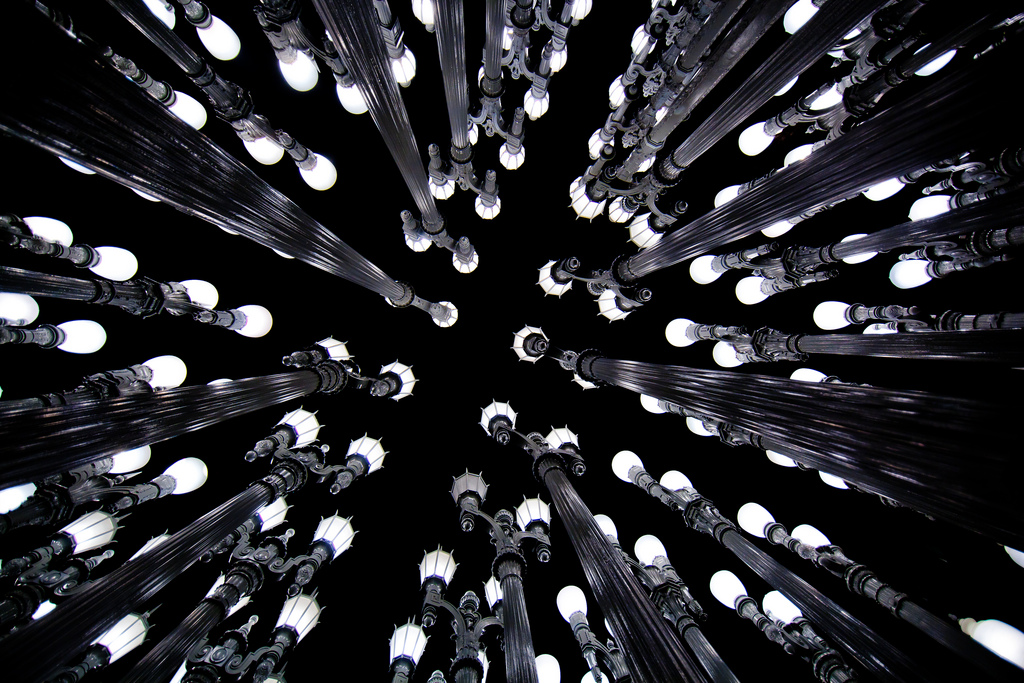

[Photo, “Heart and Wires“, by Thomas Hawk licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.]