In September 2013, Hybrid Pedagogy published an e-book of graduate student essays focused on student experiences in MOOCs — from EdX, Udacity, and other xMOOCs, to improvisational MOOCs created by the students themselves using open web resources. The full collection, Learner Experiences with MOOCs and Open Online Learning, was published via GitHub. The following article from Cindy Londeore is one of the essays from that volume. You can read more about the e-book in George Veletsiano’s introduction, “How Do Learners Experience Open Online Learning?”

Dropout. It’s such a nasty word. The high school dropout rate is held up by reformers to bolster their argument that the American public school system is failing. Massively Open Online Courses (MOOCs) have an expected 90% dropout rate which is not considered a problem. This juxtaposition begs the question; when is dropping out not a big deal?

Individuals who join a MOOC are described as being part of course enrollments. However, this is confusing and fallacious, as the term “enrollments” in a traditional in-person course implies a level of commitment not necessarily present in students who enroll in a MOOC. Initial enrollment in a MOOC is more akin to all the students who read a description of the course in the school catalog, and consider taking it. MOOC students who submit the first assignment may be a better comparison to initial enrollments in a physical class. Indeed, if the numbers of students who scored more than zero on the first week’s materials is used as a starting point, the dropout rate falls to 75%. By the end of the course the numbers are consistent with an in-person course. Only 10% of the students who attempted the final exam failed to earn a certificate. Students who enroll in traditional classes have made a commitment to attempt the work outlined in the syllabus. Students who enroll in a MOOC have done little more than express a passing interest in the topic and may feel no need to ever revisit the course.

I participated in two courses over the last few months that were very much alike in terms of course structure and assessment mechanisms, but my experiences in these two courses were very different. The first course became a chore that I quickly abandoned, but the second was so interesting that I finished the course and earned a certificate, even though I was under no obligation to do so.

Semantic Web

The first course I enrolled in was Semantic Web taught by Dr. Harald Sack and offered directly by the Hasso-Plattner Institut in Germany. The course description said that we would “learn the fundamentals of Semantic Web technologies. [We would] learn how to represent knowledge and how to access and benefit from semantic data on the Web.” Prerequisite knowledge needed for the course included a “basic knowledge” of web and database technology, and the foundations of logic.

Semantic Web was a six-week course with about 90 minutes of video lectures and one homework assignment each week. There were occasional references to additional reading that the students could purchase, but no reading materials were provided online. After each 10-15 minute video segment there were a couple of questions that were worth points toward the final total. If one answered these questions wrong, the wrong answers were marked, but no explanation of the correct answer was provided. Students could re-submit these small quizlets to improve their scores.

The weekly homework was more like a weekly quiz. Students were allowed one attempt and had a 60-minute time limit starting at the time they opened the quiz page. There were exams scheduled, but I left the course before any occurred.

The first week’s worth of lectures were interesting, mostly outlining the challenge of how to differentiate between an actual object and information about that object. I was expecting the lectures to continue in this vein, perhaps with a discussion of the changes needed in the conceptual design of the web to accommodate this new way of thinking. However, the lectures were instead about the specific programming code needed to execute the changes. I quickly became overwhelmed. The information presented in the lectures was not sufficient for me to correctly answer or sometimes even to understand the homework questions. The time limit made me feel like I couldn’t go back and review once I started a problem set.

By the third week it didn’t matter how much time I was given for the homework. It was clear I did not have the background knowledge needed. At this point I had a choice. I could either spend time in an effort to learn the prerequisite material along with the central concepts of the class, or I could drop out. I could see no reason to expend that kind of effort, so I dropped out.

I overestimated my grasp of the prerequisites in Semantic Web. My overestimation was based on the course description, and their use of the phrase “basic knowledge”. If the prerequisite skills had been phrased in a more active manner, then I would have had a more accurate understanding of what I would be required to do.

Regardless of where I place the blame, if I had made a similar mistake in a traditional course, I would have been faced with penalties for dropping out. At the minimum I would have had to find another course to make up the credit hours.

Model Thinking

The second course I enrolled in was Model Thinking taught by Dr. Scott E. Page and offered by Coursera. The course description said that the course would “present a starter kit of models … The models covered in this class provide a foundation for future social science classes, whether they be in economics, political science, business, or sociology. Mastering this material will give you a huge leg up in advanced courses.” Students needed to be “very comfortable” with algebra, but no calculus was required.

After my experience in semantic web I was somewhat hesitant to enter into another technical-sounding course. The introductory videos for both courses were very general and concept driven, so how did I know I wasn’t just going to get in over my head again? I went ahead and took the plunge into Model Thinking because of one advertised aspect: modularity. Dr. Page explained that for the most part each module we studied in the class would be independent of each other. If I failed to grasp the ideas of one section, it would have no impact on my understanding of the next section.

Model Thinking was a ten-week course with about 90 minutes of video lectures and one homework assignment each week. Additional reading materials were provided, often mirroring the content of the lectures. During some of the 10-15 minute video segments the lecture would stop and a question would be provided. If I got this question wrong, I could try again. An explanation of the correct answer was available after it was selected, or after all the other options were exhausted. These questions bore no credit in the class and were provided as a means to self-assessment.

The weekly homework was low stress. There was no time limit for completion. I was allowed to save my work and return later. For each homework, I was allowed three attempts and the correct answers and explanations were given after the first attempt. The questions asked in the homework were fairly basic. Usually I was asked to complete sample calculations to go with the model of the week. I did not find the questions difficult if I had watched the lectures. When I did get questions wrong, the feedback was helpful to me because it pointed out some crucial aspect of the assignment that I had missed.

Some of the other students complained about this system on the discussion boards. They felt that their effort was devalued if other students could potentially submit a blank homework, then copy down the correct answers and resubmit for a perfect score. Unscrupulous students could certainly have gamed the system in this way, but I fail to see the motivation for doing so. The completion certificate is not worth credit towards any larger degree, nor is it supposed to indicate a certain skill level. It is simply a personal reminder of a completed task. I also fail to understand the motivations of those complaining about the flaw in the system. There were an unlimited number of completion certificates available, so if some people want to obtain one by fraud, what difference does it make to someone who obtains one through actual learning?

The midterm exam was slightly more formal. I was still allowed three attempts, but the specific questions presented would change between each attempt. After I submitted my exam the first time, hints were provided for each question. The correct answers or full explanations that were provided after submitting a homework assignment, however, were not provided for the exam.

I found the material in this course so interesting and accessible that I went back to listen to the new lectures even though the time period for this reflection project had expired. I continued doing so, and I was able to successfully complete the course and receive a certificate.

In retrospect…

Both courses used more or less the same presentation structure and had more or less the same assessment tasks. So, really, what was the difference? Why did one work and the other didn’t?

The essential difference was the set of expectations I had formed based on the descriptions of the two courses.

I believed that I was qualified for Semantic Web. The prerequisites stated that students needed to have “basic knowledge” of XML and several other types of language markup. I am familiar with what XML is and the kinds of things it can do, so I believed that I met the requirement. After I got in to the class it became apparent what the instructors meant was that students would need to be able to write and analyze XML markup before taking the class.

At the start of Model Thinking, the prerequisites were listed in more active language. The instructor stated that I would need to be able to do algebra-based exercises and use some ideas from calculus, but not be asked to solve calculus problems. More importantly, the content of the course adhered to these stated prerequisites. The homework and exam questions frequently required calculation, but only the algebra-level difficulty they promised.

The modularity of the Model Thinking course worked for me as well. I knew that even if I struggled with one section, the next would be on a different topic with different ideas. For example, I was unable to participate in the course at all for the week after the midterm but when I returned I didn’t feel behind in the class. I was able to pick up the next module and continue from there. I had to go back to that skipped week to answer the corresponding questions on the final exam, but the modularity provided more flexibility to the course since I didn’t have to play catch up immediately. This type of modular construction would not work for all topics, but for survey classes like this one I think it works well. Without this structure, I might have abandoned the class after one missed week.

I’m a dropout and I’m ok with that. MOOCs offered me the opportunity to show up for a class, and only stay as long as I was still learning. I learned a fair bit from the first few lectures of Semantic Web, so the experience was not a waste. However, if I had stayed, I would have had to rely heavily on the discussion boards for explanations of prerequisite materials. I don’t know if that particular community would have been receptive to such requests. Dropping out also allowed me to move on to Model Thinking which was much more accessible. I like that I am not obligated to stay in any particular MOOC. I am free to spend my time on courses that are well suited to my interests and abilities, without penalties for trying something new.

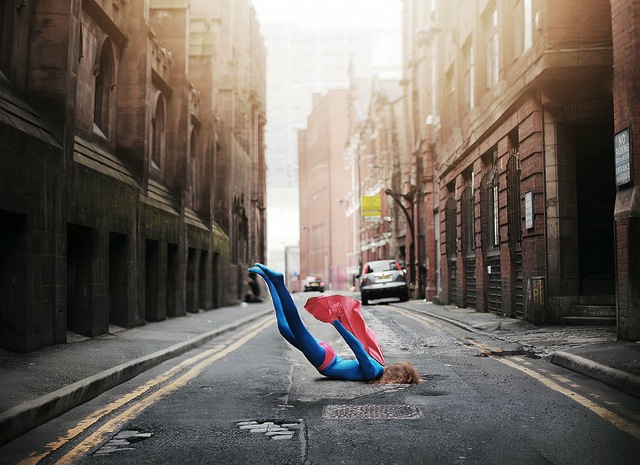

[Photo by Brett Jordan]