From all the jails the Boys and Girls

Ecstatically leap—

Beloved only Afternoon

That Prison doesn’t keep

They storm the Earth and stun the Air,

A Mob of solid Bliss—

Alas—that Frowns should lie in wait

For such a Foe as this—

— Emily Dickinson

Sometimes all you need is a Petri dish to grow an epidemic.

The point of any pedagogy is not the length of the course, size of the classroom, the headcount, or the completion or attrition rates. Pedagogy is unfazed by numbers; it is never outweighed by scale. Good pedagogy can be enacted in a room with one or two students, or in an online environment with thousands. This is because pedagogy is responsive, able to grow to the space it must inhabit, and its goal is a shift in thinking, which is spreadable by a single learner or by ten or by tens of hundreds.

Student-to-teacher ratio is a funny metric — funny because it oversimplifies a set of very dynamic interactions, privileges the student-teacher relationship over student-student relationships, re-enforces the centrality of the teacher, and underestimates the power of peer-to-peer learning. When we praise the 7:1 ratio of a liberal arts college or criticize the 100,000:1 ratio of a MOOC, we’re profoundly missing the point. The obsession with ratios confuses the issue and interferes with the work of critical pedagogy.

Critical pedagogy is predicated on the empowerment of students and the fostering of conscientization within learners, especially as that consciousness is turned toward power, authority, and the potential for knowledge to become freedom. The student becomes an explorer, a contemplative, a pedagogue, and an integral part of the intellect of the course.

The learner is never alone in this endeavor. Meaningful relationships are as important in a class of three as they are in a class of 10,000. In fact, the best pedagogies are co-produced and arise directly from these relationships. Dave Cormier argues that “curriculum is not driven by predefined inputs from experts; it is constructed and negotiated in real time by the contributions of those engaged in the learning process.” Jesse notes similarly, “There is no ‘head of the class’ in an online learning environment, not even the illusion of one.”

Learning is not transactional. Unfortunately, capital has fueled most of our discussions about class sizes and student-to-teacher ratios. Many administrators and investors insist that larger classes are a sounder financial investment, while teachers afraid for their own livelihoods rally against the drift toward stadium-size lectures, massive online offerings, and 35-person writing “seminars”. Too often, though, the complaints about increasing enrollment caps center not on the pedagogical value of small classes but on the difficulty teachers have assessing large groups of students and our worries that massive courses will necessarily mean fewer jobs for teachers. To be clear, we would not argue for creating 35-person writing “seminars” or cutting teachers (student-centered does not mean teacher-absent). What we would argue is that open education and critical pedagogy demand a reconsideration of what’s important in matters of scale.

The podium is not a cash register where attendance — not only in terms of presence, but also participation, assent to be tested, and completion of assigned work — is exchanged for praise, a grade, or a credential. Learning should be a lively exchange that looks less like capitalism and more like poetry. As Emily Dickinson writes, learning should “leap” and “storm” and “stun.” It is a “Mob,” a “Foe.” Learning “lie[s] in wait” and “doesn’t keep.” The “jail,” “Prison,” or “keep” is the institution (of education and of grammar) from which Dickinson’s lines emancipate themselves to join the unnumbered throng. The epigraph to this article describes students in school, all the more ecstatic for being also unruly.

Students are not a finite resource, except insofar as the population of the world is a finite resource. And more people want access to education than our institutions can currently accommodate. This isn’t to say that we should forget quality and turn abruptly toward mere accommodation. We need, instead, to build and guard space for learning at every scale, which means championing the work of teachers, while also encouraging peer-to-peer learning and trusting students to take ownership of their own educations.

Underestimating students is an epidemic, one that even critical pedagogues and so-called student-centered classrooms can easily fall victim to. This happens at every scale. It’s especially egregious, though, to underestimate students in classes of 20 or 10 or 5, where the student-to-teacher ratio creates more space for the voice of the teacher and less critical mass for student revolt. Watching a teacher drone incessantly to a room of 10 bored-to-death students makes even a TED Talk look blissfully interactive.

The work of trusting learners looks different (but is equally important) in a MOOC, where the teacher can sometimes be several nodes removed from the learner. In a class of 10,000, the teacher must be all the more dramatic when they step back from the podium, lest they allow themselves and their students to be swallowed up by the cult of the expert, as happens in most (but not all) MOOCs. Pedagogies of scale should be inspired by the same basic premises that dictate all the best learning experiments: 1) learning is inherently social; 2) learning doesn’t happen inside containers like classes but between them; 3) we learn best when able and encouraged to critically interrogate the platforms for our learning.

These are the principles that have driven our experiments with MOOCs. Our goal with MOOC MOOC was to start a conversation, to reflect at a meta-level on the nature of massive open online courses. We created a mini-MOOC, an experience that lasted a mere 7 days in August 2012 and 7 days in January 2013. MOOC MOOC was architectured to be a catalyst. Its power as a learning tool is not in what we built but in what rose up around it. The course was designed to outgrow its container, and was just brief enough to make space (and leave space) for community engagement and response.

Institutions all over the world offer opportunities for education in four or five basic containers: large-format lectures, small-format seminars, labs, and mainly asynchronous online classes. Most of these courses meet at regular intervals over the course of 5, 10, or 15 weeks, as though learning for each student and subject can be neatly patterned off one of these universal templates. This, though, is not how learning happens in the wild, and so we believe learning opportunities should proliferate in all manner of shapes and sizes. And, if we’re to put more energy into imagining new ways to make education bigger, we need to put as much energy into imagining new ways to make it small.

Sean writes in “The Provocation of MOOCs,” “Within MOOCs lies not an improvement upon the classroom, nor a substitute for higher education, nor a reduction of all things pedagogical. Within the MOOC lies something yet unstirred, yet unrealized. And that potential requires different personal, pedagogical, administrative, and institutional approaches than we’ve practiced before.”

We will only profit from these new approaches if we see them (and their failures) as a direct charge to investigate pedagogies of scale, the responsibilities of those who participate in learning-at-scale (teachers, facilitators, course designers, students, technologists), and the shifting hierarchies of social learning. Ultimately, every course must outgrow its container.

On June 15th, 2013, Hybrid Pedagogy offered a 24-hour MOOC, an intensive experiment in pedagogies of scale, a MOOC to end all MOOCs. To find out more, read the original announcement, follow @moocmooc, and visit www.moocmooc.com.

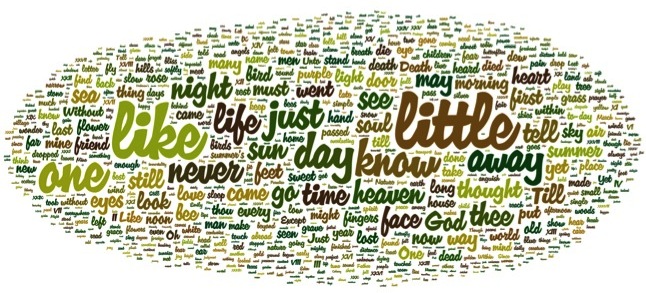

[Wordle built from the corpus of Emily Dickinson’s poetry by the students of LIT 468]