Sean Michael Morris and Josh Eyler recently sat down for a conversation to set the stage for MOOC MOOC: Instructional Design. Sean had been dipping into A Pedagogy for Liberation: Dialogues on Transforming Education by Ira Shor and Paulo Freire — a book they call a “talking book” — which was written as a kind of textual vérité. It’s less formal, and we presume less edited, than most pedagogical or academic texts, which makes it more interesting to read. As Josh says, dialogue is one of our best tools for collaboration, for working together to move our understanding of pedagogy forward. As an homage to the style of Shor and Freire’s text, and in the spirit of collaborating on developing pedagogy, we are presenting the conversation between Sean and Josh in its original, conversational format.

Sean: It strikes me that the most important pedagogical maneuver is dialogue. Unless we are willing to sit down and talk to one another, even the most critical, generous pedagogues can seem to bluster and strut.

Twitter in particular is one modern, digital platform for that kind of solo runway walk. It’s satisfying to see all the “likes” and retweets, the chorus of “amens” that follow a short rant like the one I had the other night. But I have to say it’s more satisfying when I see a response like you delivered:

.@slamteacher I’m not sure I follow. Many evidence-based practices (PBL, inquiry-based learning) are designed specifically for discovery.

— Joshua Eyler (@joshua_r_eyler) January 11, 2016

Which is why I asked for this conversation.

I want to agree that project-based and inquiry-based learning offer more opportunities for learner discovery. Unfortunately, I see both of these as still ultimately teacher-centered, authority- and mastery-driven approaches. From what I understand, inquiry is a controlled substance in inquiry-based classrooms, and projects are delimited by the requirements of curriculum and learning objectives. To me, discovery is like wandering into a forest where you’ve never been and choosing a path (or no path) through the woods. In the wandering that follows, you may discover that you are fascinated by mushrooms, or that the height of the trees stirs you, or that slugs are the most interesting thing ever. But PBL and inquiry-based learning feel much more like an invitation into the teacher’s garden. Yes, you can discover, but there are parameters for that discovery, and they’ve been set long before you ever arrived.

Student agency arrives in the form of open inquiry, which relies on learner autonomy at a foundational level. This is not just the teacher constructing opportunities or scaffolding for agency, leading the students to discover that they have certain, limited ownership of their learning. Student agency is an assumption built into the pedagogy, and comes from an integral trust of learners’ capabilities.

I would be curious as to your thoughts about how PBL and inquiry-based learning are or are not built upon student agency?

Josh: Like you, I firmly believe that curiosity and discovery are the foundation for learning. Students need to wonder; to be puzzled; to try, fail, try, fail, and try again in order for them to build knowledge and make meaning. Much of the discussion here, then, probably comes down to the issue of terminology. For me, PBL and inquiry-based learning are large umbrellas under which sit a variety of strategies. Certainly, as you say, there are some courses where activities might be rooted in discovery, but the discoveries are either already predetermined by the instructor or there is so much structure that it inhibits the process itself.

On the other hand, in just a few minutes I am heading over to take part in a pitch session for our ENGI 120 course. ENGI 120 is a Freshman Design course in the School of Engineering. At the beginning of each semester, the students listen to pitches from folks at Rice and the larger Houston community. They then vote on the projects they would most like to work on and spend at least a semester trying to design a solution. In the past, they have developed mechanical limbs, housing for birds at the Houston Zoo, and a device (featuring a regular old mousetrap!) designed to treat dehydration in children in African countries. Students work in teams, and they receive guidance from Ann Saterbak and Matthew Wettergreen, two of our faculty. The answers are unknown, and there is no guarantee that the projects will be successful. Students are simply given the freedom to explore and create with the goal of making real change. This, to me, is PBL at its finest, but I am also aware that many courses look far different from this.

So it seems like the answer to your question about student agency depends on just how much an individual instructor is willing to give up control, to allow the inquiry process to unfold, to help when asked. Another way to put this would be that so much depends on the degree to which an instructor embraces the notion of constructivism, a theory of education that emphasizes the importance of students shaping their own learning.

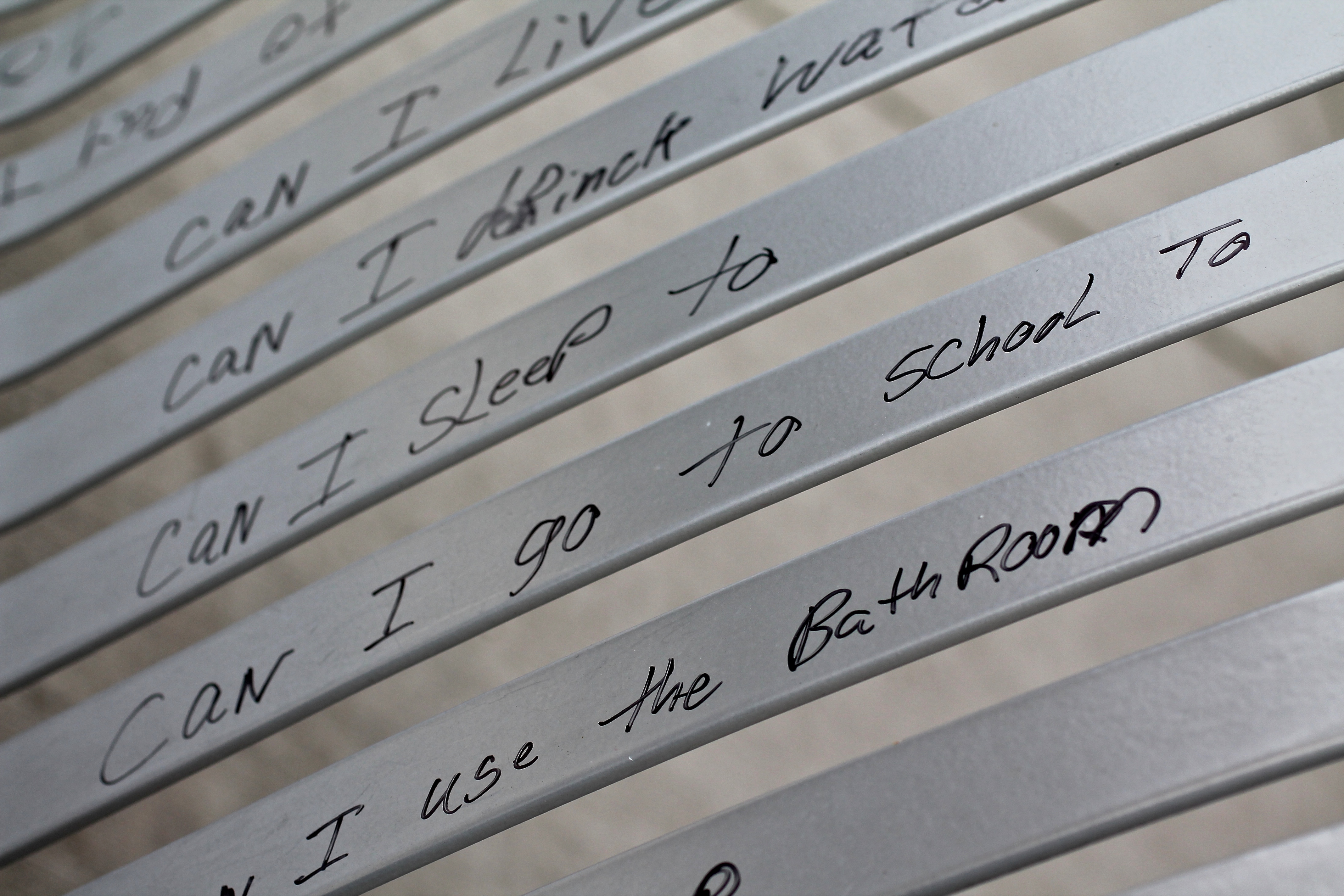

In order to embrace pedagogies like these, though, there needs to be an extraordinary amount of trust between instructors and students. Trust is such an important part of teaching.

Sean: I love the idea of students voting on the projects they want to work on! That’s a wonderful example not only of learning through projects, but also that learning ties so intimately to the work these learners would be doing in the field. I assume with such a project that invention is welcome, that it would be possible for learners to come to a solution for a problem that even their instructors might not foresee? I’d be curious to know how much guidance — or, more popularly, “scaffolding” — instructors provide learners for these projects? Any at all? Or is their role more supportive?

You raise the issue of control, that surrendering control may be not only an individual choice but, perhaps, even a personal one. Teaching is a highly personal craft, I think, the way that parenting can be. Few teachers like to be given suggestions — “Oh, in that situation, I would do it this way”, or “Have you tried…?” or “What I do is…” — and I think the suggestion to let go some authority and control is one that’s very hard to hear. I recently wrote to a colleague that “you can’t hand over all the responsibility and then take away authority”. Teachers usually consider students responsible for their grades, their performance, their learning, but don’t give them the authority they require to actually manage that responsibility. Do you see what I mean?

Designing for discovery is tricky business without that surrender of authority. It’s not a surrender of leadership — at all — but it is a surrender of that mantle most PhDs-who-teach waited far too long to wear: the mantle of “expert”. Perhaps this is also related to the issue of trust. Can we, as teachers, trust students to be authorities in their own learning, without giving over their trust in us as guides? The guide-learner relationship feels a lot friendlier than the teacher-student relationship. Do you think that PBL or inquiry-based learning, done well, can open up that friendlier relationship?

And also, how do we avoid uncritical application of PBL and inquiry-based learning, especially when the two methods have earned their place among today’s education buzzwords?

Josh: For the particular projects I was discussing above, the instructors simply provide guidance. No one knows whether or not the projects will be successful, but all work together towards a common goal.

As I said earlier, though, trust is an essential component in this model. I actually think that there is a great deal of vulnerability at the heart of any interaction between teacher and student. Students make themselves vulnerable when they say, either explicitly or through their actions, “I don’t know this. Please help me to learn.” This takes a kind of courage on their part that we don’t often recognize or take seriously enough. That space of vulnerability is almost holy ground as far as I’m concerned, because it underscores how much trust students implicitly have in their teachers. The only way to truly honor that trust, then, is to trust them in return: trust them to be autonomous; trust them to take the tools you can provide and build knowledge that surprises us with its originality; trust that they are in our classrooms because they genuinely want to learn, not because they want to be preached to or condescended to.

For most instructors, this yielding of, as you say, the “mantle of expert” can be unsettling at best and terrifying in other cases. But it is necessary, perhaps not for the wheels of the university to keep turning, though certainly to further the process of transformational learning. As advocates for education, we will have failed if we cannot help others to see this.

So your point is well taken, Sean. Any application of what we call PBL or inquiry-based learning (or any discovery-based pedagogy) must move past the jargon and embrace these notions of trust and respect. Otherwise, courses that purport to have discovery at the root will simply be teacher-led rather than teacher-guided.

Sean: I think at this point, if it’s okay with you, I’d like to return to the objection I originally voiced about evidence-based practices. As I think of them, these are teaching approaches that seek to use “proven” methods, or at least “best” practices, and that rely on sociological and psychological research as “evidence”. My bias is that teaching from evidence dehumanizes teaching, leaving teachers at a distance from learners. I’m reminded of a quote from The Qualitative Manifesto by Norman K. Denzin: “Qualitative research is a moral, allegorical, and therapeutic project.” Which reminds me of bell hooks from Teaching to Transgress: “To teach in a manner that respects and cares for the souls of our students is essential if we are to provide the necessary conditions where learning can most deeply and intimately begin.”

Does evidence-based teaching seek to care for the souls of students? Is it a moral project?

Since the onset of online learning, I’ve perceived a growing distance between teachers and learners (and already there was a significant divide). Having just finished a year working at an educational technology company, I’ve also seen from that side how learners become quantities on a spreadsheet, numbers on an infographic. I worry that researching learners and learning is not the same as knowing learners and learning. Can you respond to that? Can we consider this in terms of inquiry-based learning and PBL? Do those methods seeks to close the distance between teacher and learner? Do they address (also from Denzin) the “practice, politics, action, consequences, performances, discourses, methodologies of the heart, pedagogies of hope, love, care, forgiveness, healing”?

Josh: I would answer “Yes” to all of these questions, but there are a few qualifiers here. Evidence-based practices are simply those pedagogies that we have found to be effective after substantial research. I think as teachers and scholars we seek evidence for all kinds of things — evidence that supports our hypotheses, evidence that students are learning what we hope they are learning — so it makes good sense to me that we would also look for evidence about some teaching approaches that are better for engaging students and helping them to learn than others.

One issue, then, is this: where do we look for evidence? The research literature is a starting point, but we need to approach it with a wary eye. Isolated studies can show effects, but that doesn’t mean they are broadly applicable. I prefer meta-analyses like this one from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that evaluated 225 studies and determined that evidence-based active learning strategies were more effective than lecturing from start to finish. The work done by John Hattie in his Visible Learning resources is similar. Now, we can certainly intuit some of these findings, but I strongly believe that this evidence gives many teachers confidence that they are at least pursuing a path toward helping students that has some support behind it. I would be skeptical of an approach that advocated for choosing a strategy that was not supported by evidence (in Derek Bruff’s terms, “continuous exposition”) over one of these other, evidence-based practices.

That said, we also find evidence in our own classes with our own students. We see what works with and for them, and we test new pedagogies as others seem to be falling flat. I just think it’s important to start by trying out strategies that have been found to be effective by folks who have been studying these questions for the breadth of their careers.

The problem, to my mind, is if a teacher employs evidence-based teaching approaches only because they are evidence-based without paying attention to what is actually working for students. Evidence-based strategies can be just as morally focused, just as interested in caring for the soul, as any other pedagogy. We absolutely must get to know our students, empathize with them, and understand fully and completely that each one is a human being who brings her or his cares, worries, hopes, and fears into our classroom. But, beyond this, we just as surely need to think about the ways in which these students will learn and the techniques we can try to help them. Evidence-based strategies are an important starting point for this.

Sean: This is a great conversation. Thank you for engaging with me so frankly. In the interests of “time”, if you will, I just have one more piece I’d love to hear your thoughts about.

If, as you say, discovery-based learning must “embrace these notions of trust and respect” with regards to learners, where along the line do teachers learn to trust and respect themselves? In other words: how do we teach discovery when our teaching is heavily informed by evidence? “Best practices” flow outward, I think. If we employ them, we teach them. If our work as teachers is not exploratory, if we cannot trust ourselves and our own (unverifiable, anecdotal) evidence, how will we help learners do that?

What do you think?

Josh: In The Courage to Teach, Parker Palmer says something that I think applies directly to your question:

Authority is granted to people who are perceived as authoring their own words, their own actions, their own lives rather than playing a scripted role at great remove from their own hearts….Authority comes as I reclaim my identity and integrity, remembering my selfhood and my sense of vocation. Then teaching can come from the depths of my own truth–and the truth that is within my students has a chance to respond in kind. (33)

Although I don’t necessarily agree with everything Palmer says in this book, I find this passage to be so important. The notion of individual truths responding to each other, for me, lies at the core of what it means to be a teacher. We need first to understand what we value as educators and what we, uniquely, can bring to our students. This acknowledgment then leads to the kind of connection you were discussing earlier, as we use our “sense of vocation” to help our students achieve the extraordinary things of which they are capable. As we discover our own best teaching methods, we can model for students the discovery process, which–in many ways–is a kind of intuition that needs to be built over time, just like effective teaching. Such authentic interactions should stem from our own observations, but they need not be impinged by external evidence. Indeed, that evidence can give us an added bit of the courage Palmer writes about.

As you indicate, I think developing this trust in ourselves can be difficult. We try out new approaches, and we learn, little by little, to trust our instincts in working with students. We observe which strategies students respond to, and we learn how to make small or large adjustments to maximize learning. None of this is mutually exclusive from adopting evidence-based pedagogies. I still believe that these should be a starting point. But, in the end, discovering how to trust ourselves and–by extension–our students takes time, takes patience, and is absolutely necessary.

I really appreciate the opportunity to talk to you about these issues, Sean. I’ve learned a lot.