Ralph Waldo Emerson, from “The American Scholar”:

The state of society is one in which the members have suffered amputation from the trunk, and strut about so many walking monsters, – a good finger, a neck, a stomach, an elbow, but never a man.

Because the Internet is everything, it has always lacked coherence for me. More available than things in their entirety are blurbs about things, captions, dialogues about things; or more removed, dialogues about blurbs about things. I’m a nontraditional educator who was educated traditionally, so I tend to think about things in their entirety, and the relationships of coherence created between those things. I canonize, holding up certain works of literature as both cornerstones and harbingers of academic dialogue. The works of Shakespeare and Dickens converse with the works of Woolf and Hemingway and give them meaning. But a quote from Shakespeare tossed into the muddle of all the quotes from all the books in English loses its lucidity and relevance. And this is exactly what the internet does.

A canon serves as a tool for preserving models of good thinking, good writing, and moments in literary or scientific history that were so significant as to remain relevant today (and which promise to remain relevant into the future). Arguments have been pounded against traditional canons founded on their racial and gender biases; and part of the response to the canons of privileged white males has been the establishment of canons of women’s literature and history, ethnic literature and history, and more. As thinkers, we canonize. We bookmark the great moments, thoughts, and words that signal turns in our histories.

But more than that, the great works bookmark themselves. Ralph Waldo Emerson writes that: “The permanence of all books is fixed by no effort, friendly or hostile, but by their own specific gravity, or the intrinsic importance of their contents to the constant mind of man” (“Spiritual laws”). Important works, thoughts, and moments, in other words, adhere to the brain of society in ways that make them permanently relevant, no matter how obscure or dead the source of that work becomes. The work itself lives on, becoming canon in the brains of scholars, presidents, high school students, scientists, and soccer moms.

The Internet has yet to create a work of more than passing significance, something that may be passed from its creator generation to later generations. Creation happens for its own sake online, and not for the purpose of long-term preservation or conservation. According to a study cited by Aran Levasseur in his article “Why We Need to Teach Mindfulness in a Digital Age”, the average American “consumes 34 gigabytes of content and 100,000 words every single day.” That’s like reading a good-sized novel once per day. That’s not only a lot of information, it’s a lot of information that we can’t possibly recall, adequately process and integrate, or preserve. Most of those words we are probably not even aware we’re exposing ourselves to; and some of them we are only peripherally aware of authoring.

Jesse and Pete have talked recently about preservation and curation through services like Storify, a kind of information Rolodex for every thought you have and meet that you wish to keep track of. This is a habit that strikes me a bit like hoarding. Bookmarks upon bookmarks of stored information one will never have the time to go back and review; primarily because one is too busy collecting more bits and pieces. Dialogues about blurbs about things.

But there are bits and pieces that get stored collectively, by a majority of people on the Internet. And those are memes. Memes seem to come about spontaneously, as though growing not from the mind of any one person or organized group, but from the material of society itself. Internet memes show up unannounced in feeds, on walls, in e-mail, and eventually in conversations that take place entirely outside the Internet. They get pinned in the group mind, not just in the individual mind, and seem to – sometimes perversely – join us together. LOLcats. A talking dog. That guy who dances through different eras of music. But also a significant speech by Charlie Chaplin, an amazing piece about American education, and the It Gets Better project. Everyone knows these, everyone talks about these; and knowledge of them signals a kind of social and digital literacy not unlike the way knowledge of Chaucer or Hemingway, Moby Dick or Jane Eyre, signals literacy for the student of English.

Memes are the canon of the Internet.

But do they serve to form that dialogue of coherence that traditional canons create? Do they have that “specific gravity” that casts their relevance far into the future? When we consider digital pedagogy, we have to consider the nature and meaning of the digital texts created on the Internet. In an academy that can feasibly work with any pop culture phenomenon as material, will there one day be a class, or section of a class, dealing with the honey badger meme, orRickrolling?

In a previous article, “We Are All Made of Web Sites,” I spoke about how students today are concatenations of web sites. Likewise, student culture is creating itself as a rapidly changing body of memes, both serious and parodic. Like the brains of humanities students who cut their teeth on Jane Austen and Wordsworth, the brains of the students educated by memes are both influencing the educational system and being influenced by instruction that does not acknowledge the presence and relevance of Internet memes in their lives. Disconnection has never served learning or teaching well, nor students or teachers. It is, then, worthwhile to acknowledge the meme as a digital creation due inspection and credibility, the same as any canon.

In their recent announcement about the #DigPed discussion group, Jesse and Pete paraphrase Howard Rheingold saying that he “argues that our digital practices have the ability to become vapid or illuminating.” This is the question we must pose to the meme-as-canon (and it is the same question we must pose to every canon): what about this work or body of work will be illuminating? Which memes, which works, create relationships of coherence worthy of the best canons? Which ones give significance to all?

And moreover, what does the canon of memes do to reunite not the various members of our world, but the various teeming minds within each of us?

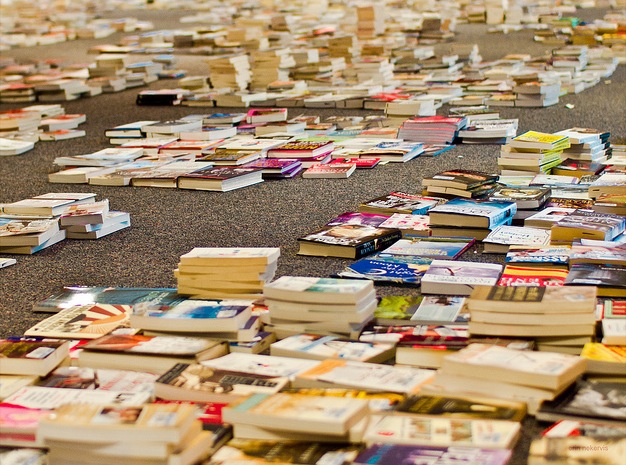

[Photo by TheeErin]